Here is an compilation of essays on ‘Green Revolution’ for class 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short essays on ‘Green Revolution’ especially written for school and college students.

Essay on Green Revolution

Essay Contents:

- Essay on the Introduction to Green Revolution

- Essay on the Features of New Agricultural Strategy of Green Revolution

- Essay on the Significance of Technological Reforms Vs. Institutional Reforms Controversy

- Essay on the Effects of Green Revolution

Essay # 1. Introduction to Green Revolution:

Agriculture can play a very important role in promoting economic development of a developing country like India. Increase in agricultural production implies increase in the production of food as well as that of several raw materials needed for different large scale industries cotton, jute, sugar, etc.

Moreover, several small and medium agro-based industries based on the processing of different agricultural crops and fruits can also be developed. Agricultural development can also ensure growth with stability as increase in the supply of agricultural crops especially that of food grains will help to control rise in their prices.

In India, the major factor causing inflation is the rise in prices of different food articles and increase in their production will control inflation considerably. Being the most important economic activity in Indian economy, the acceleration of the rate of growth of agricultural production will also boost the same of the GDP of India.

There is, however, a high degree of interdependence between agriculture and industry. While the agricultural sector supplies both industrial raw materials to industries and food to industrial workers, the industrial sector also supplies consumer goods to the people employed in agricultural and other sectors as well as important industrial capital goods, such as, different types of farm machinery, chemical fertilisers, pesticides, etc., to the agricultural sector. So, a balanced sectoral growth of the economy is always possible if there occurs simultaneous growth of agriculture and industry.

A balanced regional growth of the economy is also possible through agricultural development as agricultural activities are traditionally practiced in all the districts of all the states of India as the primary occupation of the rural people.

In a country suffering from the scarcity of Capital, as is the case of India, a lower capital-output ratio also helps to carry out agricultural development. Since agriculture is the major source of occupation in India, agricultural development will also cause increase in household income of major section of households in India.

The development of agriculture is also quite reasonably by associated with development of infrastructure in rural areas. So, while multiple cropping throughout all the crop-seasons in a year can ensure elimination of seasonal unemployment on the one hand, the works of rural development like construction of roads, bridges and irrigation canals, improvement of drainage system, contour bunding, terracing, etc. can also absorb a large section of India’s surplus rural labour force.

It has been historically proved in countries like the erstwhile Soviet Union, Cuba, Sweden, Malaysia, China and Japan that the marketable surplus of agricultural and plantation products can bring out rapid economic development and, hence, one can naturally expect mobilisation of such types of marketable surplus only through the development of agriculture in India.

However, it is also worth mentioning that agricultural development does not merely mean development through the adoption of some measures for technological reforms, but also that of drive towards institutional reforms, such as, land reforms. These measures will ensure higher agricultural productivity and employment along with social justice through reduction in inequality in the distribution of agricultural income and wealth.

The less developed countries like India and others also have a long tradition of exporting different agricultural crops and also industrial products based on agricultural raw materials. So, the agricultural sector appears as an important source of earning foreign exchange. In the present age of globalisation, Indian agricultural producers have a golden opportunity of exporting their products in the global market.

On the other hand, it may also be said that as less developed countries suffer severely from the shortage of food and, hence, from the problem of bearing the burden of import costs, increase in agricultural output can help conservation of foreign exchange through reduction in the burden of import expenses.

So, Simon Kuznets correctly pointed out three important contributions of agriculture in the process of economic development:

(i) Product contribution,

(ii) Factor contribution, and

(iii) Market contribution.

These contributions actually indicate the role that may be played by agriculture in the process of economic development. Indian planners were aware of the same and assigned priority on the development of agriculture in the First Five Year Plan (1951-56).

The production targets of agriculture were not only realised, but also exceeded in actual terms in some cases. This made the planners optimistic and over-confident about the state of agricultural development in India. The emphasis was shifted towards the development of heavy industries in the Second Plan (1956-61).

In fact, agricultural production targets were not difficult to be realised. The structural maladies of Indian agriculture continued to be unabated as both technological and institutional reforms were still neglected.

In the years immediately after independence, the Indian farmers felt the ‘patronage from the state’ for the first time towards development of agriculture by means of abolition of the Zamindary system, introduction of Community Development Project, National Extension Service and multipurpose river valley projects along with different measures for development of irrigation, etc.

These constituted simply efforts to go ahead in the path of agricultural development and it created an euphoria among farmers to increase agricultural output. But gradual shift of attention from curing structural maladies of Indian agriculture created a very deplorable situation. Food shortages and consequent burden of dependence on food imports mounted up. Indian agriculture continued to be a gamble in monsoon.

The application of traditional technology with low- yielding traditional seeds and ineffective use of organic fertiliser, inadequate availability of facilities of irrigation, continuous erosion of capability and entitlement of an average farmer, growing sub-division and fragmentation of land holdings and rural indebtedness, neglect of land reforms, low level of expenditure by the government for rural development, etc. factors caused a process of agricultural retrogression in India.

Few years of successive droughts in the early and mid-1960s worsened the situation further. The fall in purchasing power of rural consumers also appeared as a major contributory factor behind the occurrence of industrial stagnation and retrogression in India.

These failures in agriculture and industry caused a severe economic crises in India that was deepening at a fast rate and it led to the occurrence of political crisis and instability in all the states of India. In fact, it was high time for the Union (i.e., Central) Government of India to reassign emphasis on agricultural development by reconsidering the important role that could be played by agriculture not only in order to recover Indian economy from crisis, but also to accelerate its rate of economic growth. This led to the adoption of the ‘New Agricultural Strategy’ aiming at the ‘Green Revolution’ through a ‘technological breakthrough’ in Indian agriculture.

Essay # 2. Features of the New Agricultural Strategy of Green Revolution:

The adoption of the new agriculture was initially at an experimental stage since 1960-61 when a pilot project called ‘Intensive Agricultural District Programme’ (IADP) was introduced in seven districts. Later on, it was extended to other areas and it was renamed ‘Intensive Agricultural Area Programme’ (IAAP). It included the High-Yielding Variety Programme, mechanized farming, etc.

In October 1965, its network was extended to 114 out of 325 districts in different states of India though, initially, in seven districts—West Godavari in Andhra Pradesh, Shahabad in Bihar, Aligarh in Uttar Pradesh, Raipur in Madhya Pradesh, Thanjavur in Tamil Nadu, Ludhiana in Punjab, and Pali in Rajasthan.

It was practically since the year 1966-’67 that the new agricultural strategy began to be widely, introduced in India. It was a package programme consisting of application of high- yielding varieties of seeds, water management, pest control, chemical fertilisers in addition to organic fertilisers, mechanized farming, etc. which were expected to be financed by credit facilities from financial institutions like commercial banks, cooperative credit societies, etc.

While considering scarcity of agricultural inputs of proper type, it was felt to be justified to apply concentrated doses of such inputs initially in some selected areas and to extend its application gradually in other areas of the country.

The agricultural scientists prescribed the optimum packages of application of high yielding varieties of seeds, chemical fertilisers (i.e., N-P-K) and water as required with respect to the cultivation of each different crop depending on the agro-climatic nature of each different region in each state while carefully keeping in mind the nature of soil and availability of water.

Though, initially, this strategy was mostly confined into the production of wheat, it was later on found to be extended to the production of other agricultural crops—rice, millet, potato, etc.

A careful review of this strategy shows its following ingredients:

(a) The high-yielding seeds of quick maturing type came to be introduced in cases of different crops, such as, (i) PV-18, Kalyan Sona 227, Sonalika (S 308), etc. for wheat;

(b) IR 8, PR 106, Jhona 351, Padma, Jaya Vijaya, Ratna, etc. for rice; and several other seeds for the production of different other agricultural crops. These were all of quick-maturing type, it was possible to increase the number of rotation of crops. Hence, to introduce the system of multiple cropping, i.e., to grow at least two and, if possible, three or even four different crops during different crop-seasons of a particular year.

It has been suggested, for example, after the harvesting of the Rabi crop—Potato or wheat in the end of April, the Moong of Tusa Baisakhi’— that matures within a period of 70 days—might be sown and, thereafter, the monsoon crop, i.e., khariff crop rice could be sown which would be harvested at the end of autumn and, in this way, a ‘green triangle’ would be very easily completed.

(b) The quick maturity of crops caused by the sowing of high-yielding varieties of seeds need the support from chemical fertilisers, such as, nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium (i e , the use of N-P-K).

(c) It is also observed that the quick growth of agricultural plants attracts different types of pests and, accordingly, it requires the use of pesticides for the purpose of their protection. The agricultural scientists have identified different types of diseases of crops and, accordingly, the need for applying appropriate types of pesticides.

(d) In order to facilitate the scope for multiple cropping, the minor irrigation projects like supplementary use of ground water by means of tube well irrigation or dug well irrigation and the use of surface water through tank irrigation or river lift irrigation—wherever suitable have been encouraged in addition to the major irrigation project like canal irrigation.

This has enabled farmers to practice farming during both khariff and rabi seasons. It has paved the way for creation of a well-organised structure of irrigation and, hence, it is expected to emancipate farmers from their traditional dependence on rain-fed farming.

So, the new agricultural strategy has aimed to put an end to the practice of farmers ‘gamble in monsoon’ while carrying out cultivation during the khariff season. The scope of cultivation during the Rabi season is a boon to both cultivators and agricultural labourers. For, the cultivator will grow additional crops and the agricultural labourers will have additional opportunities of employment.

So, the agricultural production and productivity per hectare area of land will increase and, hence, the burden of food imports will gradually fall. The country will be able to conserve its foreign exchange reserves and also to use it-for the purpose of importing different types of capital goods needed for, increasing industrial production and also for carrying out diversification and modernisation of industries.

The introduction of multiple cropping being aided by the development of irrigation also causes the growth of the gross cropped area and increase in the intensity of cropping. It needs some explanation in this context.

The area of farm holding that is cultivated at least once in a year is called the ‘net cropped area’. If there occurs expansion of such an area through extension of cultivation in fallow lands and culturable waste lands by means of their reclamation, then it is regarded as ‘extensive cultivation’.

It implies the increase in net cropped area. But, if, on the same net cropped area, there occurs cultivation during next one or two or three crop- seasons in the same year, then the total area under farming, i.e., the ‘gross cropped area’, will increase.

This implies the practice of ‘intensive cultivation’. So, the following two expressions are needed to be mentioned:

(i) Gross Cropped Area = Net Cropped Area + The area sown more than once

(ii) Intensity of Cropping:

So, the new agricultural strategy has undoubtedly created the scope for both extensive and intensive forms of cultivation. Under the traditional system of mono-cropping, agricultural labours are compelled to remain unemployed during the part of the that is not covered by khariff season, i.e., when the rain –fed farming is not possible.

So, it causes seasonal unemployment of agricultural labourer. But the introduction of multiple cropping eliminates the problem of seasonal unemployment as the theses agricultural labourers will have their opportunity of employment throughout the year.

(e) The new strategy has emphasised the need for application of mechanized farming at different stages of cultivation, such as, the uses of

(i) Tractor or power-tiller during the initial stage of preparation of land,

(ii) Spraying machine for spraying pesticides,

(iii) Components of tube well and the pump set for minor irrigation,

(iv) Harvestor needed at the time of harvesting the crop,

(v) Thresher for threshing the crop after the harvest is over, etc.

While the seed-fertilizer-pesticides package represents the biochemical aspect, the mechanized farming represents the mechanical aspect of this strategy. While the biochemical aspect is strictly concerned with increasing agricultural output, the mechanical aspect aims at displacement of labour with a view to reducing the cost of labour that represents the major share of the cost of cultivation.

So, this mechanical aspect of the new strategy has helped farmers to raise their surplus value, but it has also caused the emergence of the problem of technological unemployment and, thus, intensification of the problem of surplus labour in Indian agricultural economy.

The success of the biochemical aspect requires effective water management, i.e., well-directed and regulated use of water. But this is not possible during the raising khariff season. But the required water management is possible during the Rabi season when there is normally no possibility of rainfall. So, the system of minor irrigation plays an effective complementary role to the biochemical aspect of the new strategy.

It is worth mentioning in this connection mat high-yielding seeds, chemical fertilisers and pesticides are perfectly divisible inputs. So, the biochemical aspect of the new strategy is suitable for all classes of farmers owning different sizes of farm holdings and, hence, this aspect may be stated to be ‘scale-neutral’. But the mechanical aspect of the strategy clearly shows the problem of ‘non-neutrality of scale’.

For, any machine is always indivisible and, accordingly, its productive capacity may not be fully utilised by all sizes of farm holdings. For example, during the same period of any given time, the capacity of tilling the soil by a tractor is more than four to five times higher compared to that by a power tiller. So, while the tractor is suitable for use in a large, farm holding, the power tiller is typically suitable for a small farm holding.

It is also worth mentioning that both biochemical and mechanical aspects of new technology clearly indicate that the types of inputs required for the new technology are highly expensive. So, it is very difficult for small and marginal farmers to adapt and apply this new technology on account of their economic inability.

But rich farmers owning large farm holdings do not face such difficulties. Moreover, rich farmers have easy access to commercial banks and, hence, they can borrow the required amount from banks whenever needed. But the poor small and marginal farmers find it difficult to borrow from banks as they fail to mortgage the required security for loan and also to arrange any guarantor for their loan.

However, it is comparatively easier for poor small and marginal farmers to reap the advantage of the biochemical aspect of the strategy as it offers the advantage of use of divisible inputs in accordance with their different sizes of farm holdings.

These farmers can arrive at a compromise solution by combining the use of the high yielding seed-chemical fertilizer-pesticide package with the use of traditional technique of using bullochs and ploughs for tilling land and also by using sickles at the time of harvest.

These farmers, however, find it difficult to cultivate during the rabi season on account of their economic inability to create own structure of minor irrigation. While rich farmers can easily install shallow tube wells, it is difficult for poor farmers to do so.

There has widely developed a practice among poor farmers to hire tractor or power tiller and different other types of farm machinery at high rental charges and even to purchase water at high rates from shallow tube wells located m adjacent lands owned by rich farmers.

These quite naturally increase the cost of cultivation of poor farmers. So, considering the emergence of all these possible problems, different state governments have come forward to install deep tube wells and clusters of shallow tube wells in the interest of poor farmers who can secure water for irrigation from such sources at low subsidised rates of the government.

The formation of farmers’ service cooperative societies-being largely financed by bank credit-is also encouraged by the government in villages in order to enable farmers to have an easy access to the practice of mechanised farming as well as to the sources of minor irrigation. But the growth of farmers’ service cooperative movement has been largely limited till now.

(f) There are, however, some other aspects of the new strategy. The government has offered price incentives to farmers by way of upward revision of procurement prices which are otherwise known as support prices. The facilities of processing, storage and marketing are also being extended and developed in order to encourage the growth of agricultural production and to put it to a profitable use.

The government was also aware of the constraints towards the availability of bank credit So, the government decided to nationalise the commercial banks in large number The first even of bank nationalisation occurred in India in 1955 when the largest commercial bank called.

The Imperial Bank of India’ was nationalised and renamed as the ‘State Bank of India’ However in order to have successful implementation of this new strategy and for several other reasons, bank nationalisation occurred at different stages in India-fourteen banks in 1969 six banks in 1980 and one in 1987.

The nationalised banks have assigned priority towards agriculture and small scale and cottage industries in cases of offering bank credit. This has created a great opportunity to small and marginal farmers to adapt the new agricultural strategy.

Essay # 3. Significance of Technological Reforms Vs. Institutional Reforms Controversy:

The term ‘Green Revolution’ refers to a sustained and continuous increase in yield per hectare area i.e., a type of yield per hectare take-off in traditional agriculture. There occurs an upward shift of the production function as a result of technological progress, i.e., the productivity of existing resources, s raised.

The biochemical aspect of the strategy of Green Revolution implies increase in the productivity of land while its mechanical aspect implies the rise in capital-labour ratio as this technological progress is both capital augmenting and labour-saving in nature. However, the biochemical innovations increase costs while technological innovations reduce costs because the former requires labour as a complementary input while the latter displaces labour.

A group of experts of the FAO once termed ‘Green’ Revolution as an alternative to the Red Revolution, i.e., this strategy of ‘technological revolution’ as a means of transformation of traditional agriculture is indeed as an alternative to the ‘institutional revolution’ caused by land reform which is championed by communists-the bearers of red flags.

This argument can be challenged, as an ‘agrarian revolution’ is the basis for development of a capitalistic system It is the historic task of capitalists to do away with all forms of feudal production relations as capitalism can develop only if the precondition of complete destruction of feudalism is satisfied Hence, it is the task of capitalists to complete the ‘bourgeois democratic revolution’ a part of which is the implementation of land reform.

Such land reforms have occurred in all the advanced capitalistic countries of today, and it started since the dawn of Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution could never occur under the system of ‘feudalism’. It is only in countries where the capitalist class neglected the implementation of land reforms, the communists had to come forward to implement it as a part of the ‘people’s democratic revolution’ that occurred in China and in some other countries.

In fact, there cannot be any clash between technological reform through the strategy of Green Revolution and institutional reform through that of land reform. These two have a relation of complementarity and one does not contradict the other. If land reform is not accompanied by technological reform, then it will have adverse effects upon the economy.

The implementation of land reform unaccompanied by application of improved agricultural technology will ensure social justice and equity while neglecting the consideration of improvement in productivity. On the other hand, the implementation of the new agricultural strategy of green revolution stressed only on the application of better technology while the simultaneous need for implementation of land reforms was totally neglected throughout India-excepting in the two states of Kerala and West Bengal.

Land reform does not only mean the offering of ownership of land to actual tillers of the soil, but also means the consolidation of hitherto scattered sub-divided and fragmented land- holdings into large scale farm holdings, formation of cooperative farming societies, security of tenant farmers, etc. So, if these measures are adopted, these will ensure a combination of measures for better organisation and improved technology.

Hence, these will help both rich farmers owning large farm holdings and poor small and marginal farmers to enjoy advantages of the ‘Green Revolution’. The neglect of institutional reforms has practically deprived poor farmers to enjoy these advantages. Accordingly, Green Revolution failed to ensure equity and social justice and, instead, it has increased economic inequality between rich and poor farmers.

So, it has to be remembered that if the improved technology is to be applied, then the farming organisation must be capable of adapting it. If the farmer is unable to bear the cost of cultivation, the objective of attaining higher productivity will not be realised.

The question of effective water management is also very important. Water management can succeed if cropping patterns followed by farmers are identical. Otherwise, the plot of land practicing high water intensive cultivation of crop will cause problems to adjacent plots of land practicing low water intensive cultivation of crop through seepage of water.

Farmers should, therefore, be trained with respect to effective management of water resources. Excessive and indiscriminate use of groundwater by farmers may cause a severe threat to its utilisation in many areas and, hence, a severe problem of shortage of ground water may occur. This will create severe environmental hazards.

Since institutional reform does not only mean land reforms, but also the measures for different other types of organisational improvement, such measures cannot be neglected. For example, the problems of storage, transportation, marketing and credit are very acute in rural areas. Despite huge rise in output by applying improved technology, many farmers fail to sell their crops at remunerative prices.

Here, the fault does not lie with the technology, but with the lack of access of farmers to better institutional arrangements. So, D. P. Chaudhuri rightly remarked that “land reforms with appropriate changes in the capital market and rural institutions would make possible maximisation of output and productivity growth completely consistent with reduction of inequalities of income distribution”.

Essay # 4. Effects of Green Revolution:

The effects of Green Revolution can be classified into two parts—beneficial and adverse effects. These may be separately discussed, in brief:

[A] Beneficial Effects:

The beneficial effects of Green Revolution are:

(i) Shift from Traditional Agriculture:

A revolutionary impact of Green Revolution is that it has gradually broken away Indian agriculture from its traditional practices and paved the way for its modernisation. Thus it has raised total agricultural output and productivity per hectare unit of land and per unit of labour. The farmers practicing modern technology could, accordingly, increase their household income considerably.

(ii) Significant Change in Cropping Pattern:

The new strategy introduced the system of multiple cropping and, hence, it brought out significant changes in the cropping pattern of India. Besides the principal crops like rice, wheat, jowar, bajra and maize and also potato farmers have shown increasing interest in producing different types of pulses, oilseeds and vegetables. These are usually grown during a period of 60 to 70 days, i.e., during the interval between Khariff and Rabi seasons and also between Rabi and Khariff seasons.

(iii) Increase in Production and Productivity:

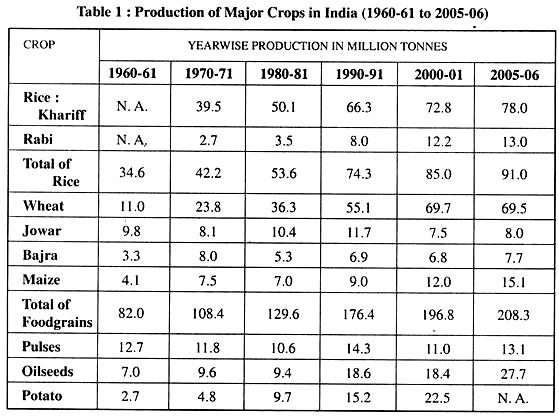

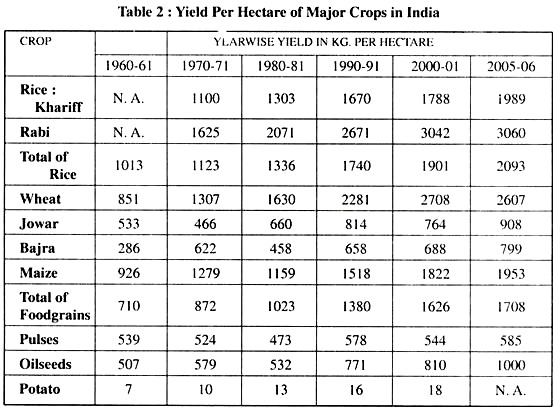

The application of high-yielding varieties of seeds and other inputs as prescribed in the strategy has helped to raise agricultural production and productivity substantially. This is observed from figures in Tables 1 and 2.

Figures in Table 1 and 2 show how, as a result of adoption of this strategy, both production and productivity, i.e., yield per hectare of principal crops, have increased if we compare the figures of 1960-61 with those of 1970-71 and onwards. Here lies the grand success of this strategy.

New high-yielding varieties of wheat were developed in Mexico by Prof. Norman Borlaug and his associates. Later on, it was adopted by a number of countries where both production and productivity per hectare increased remarkably. Initially, India also decided to import such seeds from abroad.

But, later on, the research works of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) and Agricultural Universities at Ludhiana and Pant Nagar led to the invention of a large number of high-yielding varieties of seeds and their application in fields shows the success as observed in figures of Tables 1 and 2.

The leading agricultural scientist of India, Dr. M. S. Swaminathan, played the pioneering role in all these research works. In fact, the success was initially most observed in case of production of wheat which led many to use the term ‘Wheat Revolution’. However, later on, the trend of success was also observed in cases of other crops though wheat still continue to dominate in terms of the percentage rate of growth.

(iv) Reduction in Import of Food:

The success of Green Revolution in the field of production of food caused continuous reduction in India’s import of food. For example, in terms of thousand tonnes as the unit, India’s import of cereals was 3,747.7 in 1960-61 But later on this figure reduced considerably, such as, 3,343.2, 400.8, 308.3, 90.0 and 33.9 in the years to 71 1980-81, 1990-91, 2000-01 and 2005-06, respectively (Economic Survey, Govt. of India, 2006- 07, P.S. 82).

This is also a grand success as it is through the success of Green Revolution India had the experience of raising her status from a country with severe dependence on food-imports to that of a nearly self-reliant food-growing country. This reduction in import of food helped the conservation of foreign exchange and its use for financing import of different types of necessary capital goods for the purpose of developing industries.

But the problem of overpopulation has always appeared as a severe constraint to India’s development. Despite huge rise in production of cereals, the per capita net availability of cereals did not increase much as it increased from 399.7 grams per day in 1961 to only 426.9 grams per day in 2004.

(v) Change in outlook:

The modern farm technology has also modernized the outlook of farmers. Instead of using the surplus income of farms for buying luxury goods, jewellery etc. the farmers are now more interested in ploughing back it for improvements of farms.

A. S. Kahlon, in his study, ‘Green Revolution and Changing Rural Scene’ (E. P W July 30 1969) found it to the extent of 55 percent of total family income among farmers in Punjab Again W Ladejinsky observed growing interest among farmers to adopt this new strategy.

To quote him “Where the ingredients of the new technology are available, no farmer denies their effectiveness. The desire for better farming methods and a better standard of living is growing not only among the relatively small number of the affluent using the new technology: but also among countless farmers still from the outside looking in”. (EPW, December 29, 1973).

(vi) Changing Pattern of Farming:

The new technology has increased both extensive and intensive forms of cultivation. Instead of leasing out their land, the landowners have become more interested to carry out multiple cropping throughout the year and, for this purpose they are hiring labourers in exchange of payment of wages.

The rich farmers are even leasing in land from poor farmers if they are found to be unable to grow crops in the Rabi season .So the feudal mode of production is gradually on the wane in India. Furthermore, the farmers are also diverting their attention towards production of different commercial crops.

(vii) Linkage Effects:

The new agricultural strategy has paved the way for development of many industries and services. The industries producing different types of farm machinery, chemical fertilisers, pesticides, etc. are growing at a fast rate.

Moreover, different units offering repairing and maintenance services to the users of farm machinery are also growing along with the growth of trading organisations engaged in the sale of different capital inputs to farmers purchasing products of farms for the purpose of their sale to the people engaged in non-agricultural activities, etc.

[B] Adverse Effects and Limitations:

The different adverse effects and limitations of the strategy of Green Revolution are:

(i) Neglect of Institutional Reforms:

The new agricultural strategy simply emphasised on technological breakthrough while neglecting land reforms and different other measures for improving the organisational structure of farms.

Minhas and Srinivasan, in their studies, observed that the landowner farmers reaped profits of 180 percent or more in cases of cultivation of rice and wheat while it was only around 65 percent or slightly more than that in cases of tenant farmers in cases of cultivation of rice and wheat. As a result of neglect of land reforms the economic condition of share cropper tenant farmers could not improve.

The high degree of inequality in the distribution of landholdings in different states is responsible for intensification of socio-economic imbalances. The tenant farmers and small and marginal landowner farmers found it difficult to adopt the highly expensive technology while the owners of medium and large farm holdings could easily reap all the benefits of this strategy.

(ii) Problems of Labour Displacement:

The strategy of introducing mechanised farming has caused widespread displacement of labour, growing number of surplus labour and continuous fall in their money wages in the labour market. C. H. Hanumantha has found the bio-chemical aspect of the new strategy having high potentiality of absorption of labour. But Martin Billings and Arjan Singh found the mechanical aspect of the strategy to be labour-displacing and its land-augmenting effect was also found to be negligible.

They conducted their studies in Punjab. It was observed that the use of minor irrigation, say, tube well irrigation, tended to increase the demand for labour while the use of tractors or wheat reapers reduced the demand for labour.

They reached the conclusion that displacement of farm labour in Punjab was expected to rise from 55 percent in 1968-69 to 17.4 percent in 1983-84. They felt that about 55 percent of such displacement was caused by the use of tractors and pump sets and 37 percent of that was caused by threshers and reapers.

(iii) Growing Inter-Personal Inequalities:

The poor small and marginal farmers found it difficult to bear the high cost of cultivation forced upon them by the new strategy while rich farmers were able to make huge investments on improvement of land, purchase of all the necessary fixed and variable inputs needed for cultivation.

Many tenant farmers were also evicted by the landlords. So, income disparities among rich and poor farmers were mainly on account of non-neutrality to scale of production of the new technology as was observed by C. H. Hanumantha Rao.

(iv) Growing Inter-Regional Inequalities:

Different regions of India have agro-climatic variations, different systems of land-tenure, etc. Moreover, the response of farmers to the new strategy is also different in different regions. So, while Punjab and Haryana played the pioneering role in achieving success through the new strategy at the initial stage, other states lagged behind these two states.

Later on, however, some areas of Rajasthan, Western and Eastern parts of U P North Bihar, Southern region of West Bengal and a few areas of Andhra Pradesh achieved success in this field where production of different types of food grains increased considerably.

But till now different regions of these states also suffer from uneven development in agriculture. The major parts of western and southern states of India and the entire North-Eastern regions of India have failed to achieve any success through this new strategy.

(v) Unequal Coverage of Crops:

The success of new agricultural strategy is confined only to the principal food crops. But the strategy failed to extend its success to commercial crops.

(vi) Growth of Capitalistic Farming:

Different studies reveal the growth of capitalistic farming in India. The owners of large farm holdings have evicted tenant farmers and invested large sums of money for practising the new agricultural strategy. Hired labour is employed by these big landowners. Hence, the feudal mode of production and production relations has been replaced by the capitalistic mode of production and production relations.

This has been widely observed in Punjab, Haryana and Western U.P where these big farmers or Kulaks constitute former feudal landlords, retired civil servants, ex-servicemen of army, etc. A study conducted by Ashok Rudra, Majid and Talib confirmed this growth of capitalistic farming in Punjab. Hence, it has intensified inequalities in our rural economy. The new strategy promoted growth, but failed to ensure equity and justice.

Concluding Observations:

So, the new agricultural strategy has both beneficial and adverse effects. Based on these lessons, the country has now entered into the era of a ‘Second Generation Green Revolution’ by the decade of 1990s when measures are needed to be adopted to cure all these maladies.

Measures are being adopted:

(i) To extend the benefits of this strategy to small farmers

(ii) To develop dry land farming,

(iii) To spread the strategy to a wide variety of crops and to the hitherto neglected areas.

It is expected that within a period of next ten to fifteen years, this new drive will ensure a complete success of the strategy of Green Revolution with a wider coverage and also with more equity and justice.