Here is a compilation of essays on ‘Unemployment in India’ for class 9, 10, 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short essays on ‘Unemployment in India’ especially written for school and college students.

Essay on Unemployment in India

Essay Contents:

- Essay on Unemployment in India

- Essay on the Sen’s Test of Disguised Unemployment

- Essay on DU under the Production Approach

- Essay on DU under the Income Approach

- Essay on the Recognition Aspect of Unemployment

- Essay on the Measurement Problems of Unemployment

- Essay on the National Sample Survey Data

- Essay on Data from the Employment Exchange

- Essay on the Existence of Disguised Unemployment

Essay # 1. Unemployment in India:

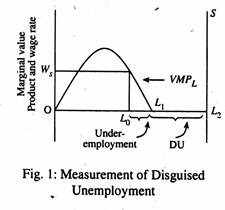

Disguised unemployment refers to unemployment which is ‘hidden’, i.e., not visible. A large number of persons who may apparently seem to be employed and look like working may not be contributing anything to production. In technical jargon, disguisedly unemployed are those who are so numerous, relative to the resources, that the marginal productivity of labour over a wide range is zero, if not negative.

The concept is illustrated in Fig. 1. The value of marginal product of labour is shown by the inverted U-shaped curve. The wage rate should equal the marginal value product at the given level of employment. Suppose, the subsistence wage level is OWs. At this wage rate, OLs unit of labour can be provided gainful (full-time) employment.

However, the supply of labour is OL2 and all are being employed, then there are L0L1 units of underemployment (their marginal value product is less than the wage rate and is declining) and L1L2 units of disguised unemployment (their marginal value product is initially zero and subsequently negative).

This situation exists exclusively, or predominantly, in subsistence agricultural sector, where family labour is largely used. So no wage payment is made. Unemployment, underemployment and disguised unemployment may result from the fact that labour in the LDCs is relatively abundant in relation to capital and the productivity of labour is usually low in most such countries in comparison with that in the developed countries.

Low labour productivity in the LDCs is the combined result of a number of factors such as:

(a) The shortage of capital and other complimentary resources,

(b) Backward technology,

(c) Lack of proper education among the farmers,

(d) Lack of training and inadequate skill and

(e) Poor health and nutrition.

Unemployment is the root cause of widespread poverty in the LDCs.

It is not easy to use the direct approach to the measurement of disguised unemployment withdrawal of labour in response to market demand for it tends to be relatively slow. So its impact cannot be easily isolated from the effects of other factors.

An alternative is to measure disguised unemployment within the framework of a specific model, assuming that the model holds (or better, after testing that its underlying assumptions are verified). This may be called the ‘indirect’ approach’.

Perhaps the most successful attempt in estimating surplus labour in Indian agriculture has been made by Shakuntala Mehra (1966). She did not test the model, which would have required checking the supply function of labour effort in peasant families. But assuming that the supply curve is flat she calculated how many could be withdrawn from Indian agriculture without affecting total output. Her methodology may now be briefly described.

Indian farms classified in terms of size show considerable variation in the volume of effort put by each worker, the intensity of work time being greater for farms with a large amount of land per head, Assuming that the largest farms, which could be expected to have the highest amount of work time per cultivator, have no surplus at all, she calculated the number of people in other farms who would be set free if the cultivators there could work for the same amount of time per head as the cultivators in the other farms, not having any surplus labour.

Mehra’s approach is based on the assumption that in family farms the shortage of productive work is shared by all and takes the form of a smaller amount of work per worker. She treats output as a function of all productive factors including labour time. She also considers withdrawal of labour keeping all factors (including labour time) constant.

The data relate to 1956-57. Since people are indivisible and a 0.5 person being surplus does not permit anyone to be withdrawn (unless farms are merged together). Mehra adds the number of the farms to the size of the ‘required’ work force to arrive at the maximal estimate of the necessary labour force and, therefore, the minimal estimate of surplus labour. The actual surplus will, of course, be larger and will lie somewhere between the minimal estimates and the uncorrected maximal estimates.

Essay # 2. Sen’s Test of Disguised Unemployment:

Amartya Sen has applied three tests of ‘disguised unemployment’ in 1971. The first one is the production approach. According to this approach a person is disguisedly unemployed if the exit of a person from the family farm leaves total output unchanged.

The second approach is the income approach. The pertinent question in this context is: Is a person’s income (including direct consumption and any other income that he receives) a reward for the work he does and will he cease to get it if it stops work? If the question is answered in the ‘affirmative’, then the person is not disguisedly unemployed.

However, if the receipt of income is not conditioned by his putting some productive effort, then he is to be treated as redundant. Likewise, if a person puts some effort in the family farm but does not derive any income, then he is to be treated as disguisedly unemployed.

The third one is the recognition approach. The question here is: does a person consider himself as employed? Do others treat him as unemployed? The conventional treatment of ‘DU’ has concentrated on the first approach only. For example, Dipak Majumdar has suggested an explanation of DU on the basis of zero MPL or zero social opportunity cost of labour. But according to Sen, various problems are associated with this standard approach. For overcoming these problems the last two approaches suggested by Sen are relevant.

Essay # 3. DU under the Production Approach:

In terms of the production approach, DU means that a withdrawal of a part of labour force from family agriculture would leave total output unchanged. This means the marginal productivity of labour, over a wide range, is zero. In spite of this, labour is being applied over this wide range. There must be some reason behind such unnatural behaviour.

Sen explains this puzzle by drawing a distinction between labour time and the number of labourers. In his view the phenomenon of DU is connected with variations in labour time per person (or ‘effort’ per person), i.e., work spreading and work stretching.

DU gets reflected in lower intensity of work, e.g., the farmer watching the bird or singing a song while sowing seeds. If three people work for longer hours, one person becomes totally unemployed. But, at present, all are underemployed, but none is fully employed.

Sen argues that a work equilibrium at zero marginal product of labour is neither necessary nor sufficient for the existence of DU. DU is said to exist if the supply price of labour time is an increasing function of work time, in which case a withdrawal of a part of the work force will reduce output.

DU is said to exist if a reduction in the labour force leaves the total work time and the level of total output completely unchanged (the reduction in numbers being completely balanced by the increase in work per person).

According to Sen, there are two ways of measuring DU in India from the production point of view, viz., the direct approach and the indirect approach. If we adopt the direct approach we have to observe whether withdrawal of a part of the labour force has any consequence on production.

The main problem associated with the use of the method lies in the difference between:

(i) Withdrawal of labour from families with a high ratio of labour to other productive resources, as when labour is attracted elsewhere through the labour market, and

(ii) Withdrawal not related to resource use such as spread of epidemics in rural areas. The impact of the former on output is in no way comparable to the fall in input in latter case.

Essay # 4. DU under the Income Approach:

If an individual derives his share of the farm income (as a member of a joint family), whether he works or not, then he is unemployed in both the production sense and in terms of income approach, too. The reason is that his farm income is independent of his work effort and his work has no relation to his income. In contrast, if a person is supported only on condition that he puts necessary effort, shares a portion of family work and does not receive any income if he quits, then he is employed in the income sense. ,

Sen’s income approach to unemployment is not concerned with checking whether a person’s income is high or low, but whether the compensation he receives is conditional on his work performance. Looked at from this angle, “a member of a joint family working in the family farm is to be regarded as unemployed if he could continue to receive economic support even if he did not work in that farm, but is to be taken as employed if his emolument would cease if he stopped working in that farm. The criterion is not whether his income is high or low, but whether his income is conditional on his work.”

Essay # 5. The Recognition Aspect of Unemployment:

At present, in rural areas one who is disguised unemployed in both the production sense and the income sense may not consider himself as ‘unemployed’ because he works and manages to survive economically. So he may not consider himself as ‘unemployed’. Such a person may have a very low intensity of work in his own farm and is in acute poverty.

Yet he does not seek employment outside his family farm and cannot even be persuaded to take up wage employment elsewhere even if it is offered to him. Since he does not regard himself as ‘unemployed’ it is not possible to induce him to offer himself as a wage labourer in the open market.

So the concept of DU is not very transparent due to the recognition aspect. Unemployment is a state of mind and depends on how a particular society values the fruit-lessens of work. And any measure of DU based on production and income is bound to be inaccurate.

Essay # 6. Measurement Problems of Unemployment:

An accurate measurement of unemployment in India is one of the thorniest problems faced by researchers and planners. The Report of the Committee of Experts on Unemployment Estimates (Planning Commission, GOI, New Delhi, 1970) to be abbreviated RCE argues that the concept of unemployment is not meaningful in the conditions prevailing in rural India. Moreover, no accurate estimate of urban unemployment is available in India either.

According to RCE estimates of growth in the labour force, of additional employment, generated by the plans and of unemployment at the end of each plan period, presented in one- dimensional magnitudes are not really meaningful.

So RCE has recommended separate estimation of different segments of the labour force, taking into account such important characteristics as region (state), sex, age, rural-urban residence, states or class of worker and educational attainment.

The Census Data:

There are three main sources of data on unemployment in case of the Indian working population:

(i) The decennial censuses

(ii) The National Sample Surveys

(iii) The employment exchange registers’ the Employment Market Information Programme.

The 1961 census found only 1.4 million people unemployed in the whole of India registers of these 0.6 million were in rural areas, and amounted to less than 1% of the rural labour force. For urban areas the per cent of unemployment were 3.25 and 1.48, respectively for males and females.

While these figures are low enough compared to those in many advanced countries, they mainly reflect the stringent nature of the test by which a person is classified as unemployed by the census authorities. For ‘seasonal work like cultivation, livestock, dairying, household industry, etc., if the person has had some regular work of more than one hour a day through out the greater part of the working season’, he was taken as engaged in work.

‘In the case of regular employment in any trade, profession, service, business or commerce the basis of work will be satisfied if the person was employed during any of the 15 days preceding the day on which the investigator visited the household. The unemployed were those who were not thus engaged in work but were ‘seeking work’.

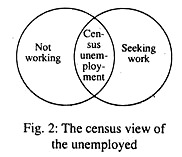

To qualify as unemployed one had to fail the test of ‘working’ and pass the test of ‘seeking work’, overcoming on the way various obstacles like being put under some other category of ‘not working’ people, such as the ‘housewife’ ‘engaged in unpaid home duties’, ST (‘student’), or B a beggar, a vagabond or an independent women without indication of source of income and others of unspecified source of existence’.

The census view of the unemployed is presented in Fig. 2. The test of unemployment is based on the intersection of two criteria, i.e., not working and seeking work. In Sen’s view, if one recognises oneself as unemployed and ‘seeks work’ but regularly does one or two hours of work in the family farm, one does not qualify as ‘not working’ and therefore has no chance of being taken as unemployed.

Similarly, if one is ‘not working’ but not ‘seeking work’ either, then again one is not unemployed. The census definition of the unemployed covers precisely those who pass both the tests.

According to RCE, “the definitions used in the 1961 census cannot be said to have caused an undue bias towards classifying as ‘unemployed’ those engaged in the non-agricultural sector, since employment in this sector is generally more stable than in agricultural and a person separated as working on ‘at least one day during the fortnight preceding the day of enumeration’ may indeed be presumed to have been in some kind of employment”.

But this prediction is contradicted by the National Sample Survey data for the same period which shows that the number of people who worked did not work on a single day during the week preceding the survey and the latter included both these who did not work a single day in the preceding fortnight and others who worked in the week before the last week but not in the last week.

Essay # 7. The National Sample Survey Data:

The criterion of unemployment adopted in the NSS is much narrower than the one adopted by the census figures. In short, due to the imposition of age restriction the NSS criterion of unemployment is based on the intersection of these sets, viz.,

(i) Those ‘not employed’ (in terms of the reference work),

(ii) Those who are available for work and

(iii) Those between 15 and 60 years of age. Due to the imposition of the second restriction, those counted as available for work in the urban areas include only people who were ‘looking for work’, rather than being just ‘available for work’.

After the 17th Round (1961- 62), it was felt that the concept of unemployment was not applicable to rural areas. This is why rural laboratory surveys were discontinued and the data on rural unemployment were obtained only from the integrated household schedule.

The term ‘unemployed as defined by the NSS is broader than the same term as defined by the Census of 1961. This is why the number of people unemployed in the 1961 Census is less than that in the Corresponding National Sample Surveys (16th round, 1960-61 17th round 1961-62).

According to the Census, the percentage of unemployment is much low in both rural and urban areas, except for urban males. The shortfall of the census figure is large in rural areas and more so for females.

The reason for this is not far to seek. As Sen has put it, “The criterion of being ‘available’ for work even if not actively ‘seeking’ work, did give the NSS a wide coverage. This is especially important in rural areas where the channels for seeking work are not always available, particularly for women, who frequently cannot seek work actively given the social arrangements. There is also the difference of the reference period being one week for the NSS and a fortnight for the census of non-seasonal activities”.

According to Sen, “For rural areas the census criterion of merely an hour’s work in each day during the busy season is, of course, a remarkably easy test to pass in order to be classed as ‘working’, thereby yielding a very narrow coverage for the ‘not-working’”.

Essay # 8. Data from the Employment Exchange:

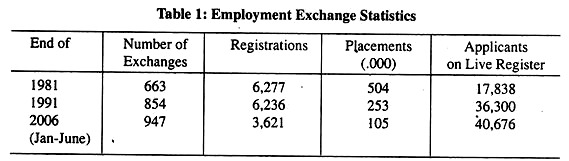

The live registers of employment exchanges also give detailed information of the number of job-seckers. See Table 1.

These figures have been used in the past by the Planning Commission in order to estimate the magnitude of urban employment in India. However, there are major problems associated with the use of these data. In truth, the same person can be employed and still look for another job.

The employment exchanges never want to know whether one is already employed or not. For this reason the number of people on the live register of the employment exchanges exceeds the unemployed on the NSS.

The differences between the unemployment figures from different sources reflect mainly the heterogeneity of the concept of employment. The live registers of the employment exchanges adopt a much broader approach than both the NSS approach and the census approach. It is based merely on dissatisfaction with one’s current state of activity whether or not one has a job. But it is narrow in other respects.

As Sen has put it, “Only those are covered who bother to register leaving out those who doubt that employment exchanges can help, or those who are too far away from an exchange. The latter is a fairly serious consideration, since most towns in India do not have an employment exchange. And the coverage of the rural areas is, of course, in effect negligible”.

Essay # 9. The Existence of Disguised Unemployment:

Does disguised unemployment really exist in India at present? Some economists have ex- pressed the view that it no longer exists in Indian economy. Under the strictest definition, a marginal product of zero (together with a positive level of consumption to ensure survival) is attributed to disguised unemployed.

Nurkse suggested utilisation of surplus labour for productive capital formation, in a virtually costless fashion. Nurkse’s vision seems less useful today. The very existence of DU has been challenged. If the zero-MPL criterion is used, it must be possible to withdraw labour without reducing total output.

Under the usual ceteris paribus condition, the withdrawal cannot be accompanied by any changes in other conditions of production. Capital equipment cannot be added as workers leave nor can the working hours of the remaining labourers be increased. This is why many development economists have asserted the impossibility of the existence of disguised unemployment under such conditions.

Of course, from a practical standpoint, rearrangements can be made, if necessary. For example, during most seasons, farm workers can work longer hours to fill the gap left by the departure of the disguisedly unemployed.

Advice of agronomists and extension specialists at moderate costs may lead to improved methods of cultivation. The usually labour-intensive means of rural production may be modified by the introduction of greater amounts of traditional capital equipment.

Any of these alterations would lead to larger output and increased incomes for farmers. But all would involve some costs. But none, in the original abstract sense of the notion of disguised unemployment can be associated with completely costless transfers of resources to highly productive activities or sectors.