Here is a compilation of essays on ‘Public Sector’ for class 9, 10, 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short essays on ‘Public Sector in India’ especially written for school and college students.

Essay on the Public Sector in India

Essay Contents:

- Essay on the Theoretical Foundations of Public Sector in India

- Essay on the Declared Objectives of Public Enterprises

- Essay on the Development of PEs: Quantitative Indicators

- Essay on the Growth of Investment

- Essay on the Performance of Public Enterprises

- Essay on the Constraints on Performance of Public Enterprises

- Essay on the Concluding Remarks to Public Enterprises

- Essay on the New Policy towards the Public Sector

Essay # 1. Theoretical Foundations of Public Sector in India:

Preview:

India adopted planning within the framework of a mixed economy to achieve economic growth and other desired socio-economic objectives. The development strategy outlined assigned the public sector an important role in the country’s industrial development in particular and economic development in general.

The strategy was brought into focus by adopting the Mahalanobis heavy industry oriented planning strategy in the Second Five Year Plan (1956-61). It was an operational follow up of the Government’s (1954) declared objective of attaining a socialistic pattern of society. The Second Industrial Policy (1956), which followed the commitment but preceded the Second Plan, envisaged a strategic role for the public sector in the transportation of India’s economy.

Due to the adoption of such a strategy, the public sector has come to occupy an important place in the Indian economy. It accounted for more than 25% of India’s GDP in 1989-90. Its share in total gross domestic capital formation fluctuated around 40% during the period 1965-95, though its contribution to domestic saving fell sharply in recent years.

From the mid-1950s the role of the public sector was considered necessary to overcome various market failures—such as the existence of natural monopolies, externalities in production and consumption, provision of public and merit goods for ensuring justice (equity) and imperfection in markets for information and knowledge. It is, therefore, appropriate to evaluate the performance of the public sector against these criteria.

Public enterprise units (PEUs) and Instruments of Policy within the broad framework of India’s Five Year Plans, public sector units (PSUs) have become a major instrument of economic policy since 1956—particularly in the context of perceived shortages of entrepreneurial and technical skill and other strategic resources and was, therefore, supposed to occupy the ‘commanding height’ of the economy.

Rage of Activities:

PEs in India cover a vast and varied range of activities. So their scope of operation is very wide. They are engaged in manufacturing, producing, distributing, transporting, and lending activities.

Organisation:

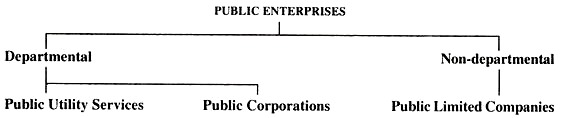

PEs have been organised under two broad categories: departmental and non-departmental.

The later fall into two sub-categories: public corporations and public limited companies:

Public utility services (Post and Telegraph, Railway, etc.) have been organised as departmental undertakings.

There are two main types:

(i) Defence institutions—which are governed by the relevant secretariat directly, and

(ii) Railways—which are governed by a board responsible to the minister who, in turn, is accountable to the Parliament.

Due to lack of flexibility and operational efficiency inherent in departmental undertakings, many developmental and trading concerns such as the Oil and Natural Gas Commission, and the Central Warehousing Corporations have been organised in the form of corporations.

The exact form of organization of PEs depends on two things:

(i) The derived degree of autonomy, and

(ii) Flexibility in their operations.

Since the company form of organisation provides a high degree of autonomy and flexibility it has become a very popular form of organising commercial, industrial and manufacturing public undertakings. Such public enterprises are registered under the Indian Companies Act, 1956. In a public limited company at least 51% of the capital is owned by the Government.

Essay # 2. Declared Objectives of Public Enterprises:

The stated objectives of the PEs were many. However, these were not mutually exclusive. These can be classified as:

1. Provision of merit goods like education and health;

2. Ownership of natural monopoly (as in case of coal, steel and oil);

3. Legal (artificial) monopoly in as in the case of arms and ammunition and railways;

4. Diffusion of private enterprises and prevention of non-competitive practices;

5. Faster development of the economy for creating employment opportunities, achieving self-reliance and ensuring equity and justice (through redistribution of wealth and reduction of undue concentration of economic power in few hands);

6. Giving entrepreneurial support to weaker sections of the society; and

7. Conservation of productive capacity as also non-renewable natural resources (like coal, iron ore and crude oil).

8. Employment protection as in the case of privatisation of ‘sick’ textile mills in the private sector.

According to Prof. Atul Sarma the growth of PEs in India has been promoted in three ways:

(i) Entrepreneurial substitution, i.e., the setting-up of PEs at the initiative of the govt.;

(ii) Entrepreneurial support through

(a) Equity participation, or

(b) Disbursement of loans, or

(c) Provision of management and technical know-how, and/or

(d) Supply of critical raw materials; and

(iii) Management substitution through takeover of private enterprises by the states through

(a) Nationalisation of sick private enterprises, and

(b) Acquisition of sick private enterprises (which are on the verge of liquidation) for rehabilitation.

Studies show that there were shortages of entrepreneurial and technical skills in relation to natural resource endowments at the beginning of the planning area. For this reasons PEs as an instrument of policy had been directed to meet the challenges of development through entrepreneurial substitution.

Entrepreneurial support provided through PEs has been largely directed to promoting private entrepreneurship for fulfilling three objectives:

(i) Diffusing monopoly,

(ii) Reducing regional disparities in the levels of industrial development (and thus achieving balanced regional growth), and

(iii) Helping weaker sections of society.

In the opinion of Prof. Sarma:

“Apart from the nationalisation of life insurance and general insurance, banks and coal mines, marginal substitution has been confined to takeover of ‘sick’ industries in the private sector, so as to optimally use scarce capital and safeguard the interests of the employees in such enterprises”

1. Reduction of Concentration of Economic Power:

It was thought that that undue concentration of economic power that would result from the uncontrolled operation of the market forces could be reduced through expansion of the public sector. It is because this would lead to an extension of public ownership of the means of production.

2. Risk-Taking:

Private investors make a higher rate of return on investment in certain risky but socially desirable projects such as exploitation of oil.

3. Investment Need:

In highly capital-intensive industries such as steel, heavy engineering, electrical machinery, etc. that would need huge investment. The private sector may not have the capacity to raise such a huge amount of capital.

4. Generation of Investible Surplus:

By adopting appropriate price policy the public sector would be in a position to generate necessary investible surplus for further investment. This would conduce to faster growth of the industrial sector.

5. Control of the Private Sector:

By producing and distributing certain intermediate goods such as coal, steel, electricity—which are used as inputs in a large number of industries it would be possible for the State to influence pattern of private investment and change in composition of private economic activity in socially desired direction.

6. Employment Creations:

The public sector was supposed to play the role of a model employment in the sense that its employment and wage policies would have a favourable effect on the corresponding policies in the private sector. In short, the public sector was expected to fulfill varied and-at times-conflicting objectives For example, the generation of investible surplus was in conflict with incurring losses to be able to supply certain inputs like steel, coal and power at low prices and maintain a high level of employment.

The subsidies involved in keeping the prices of certain inputs low involved loss. This is why it is said that loss leaders can exist only in the public sector. Moreover, investment made in the public sector during the first four decades of planning (1951-91) enabled it to reach commanding heights of the economy and produce a wide range of goods and services such as steel, coal, oil, electricity, transport and communication, finance and insurance.

A number of strategic sectors of the economy are now dominated by mature PEs that have expanded and diversified their operations, upgraded their technology and built-up a vast reserve of technical competence in a number of diverse areas.

Largely due to the expansion of the public sector India’s rank in the industrial world is quite high (16th) in 2005-06. India’s competitive advantages such as a large pool of trained technocrats and qualified manpower in manufacturing and chemical industries originate mainly from the public sector.

Essay # 3. Development of PEs: Quantitative Indicators:

In a broad sense, PEs cover all types of enterprises managed departmentally under statutory corporation form, and under the Companies Act, and owned by any level of Government (i.e. union state and local). Only data on industrial and commercial undertakings of the central Government covering statutory corporations and companies registered under the Companies Act are published annually (by the Public Enterprises Survey).

Since the Survey does not cover the departmental^ managed undertakings, nationalized banks, and Government owned all- India financial institutions the enterprises covered under the Survey account for only 23% of the total number of persons employed in all the non-departmental PEs.

Essay # 4. Growth of Investment:

The number of Central Govt. public sector enterprises (excluding banks, financial institutions and departmental undertakings such as the Railways, Ports, etc.) increased from 5 in 1950-51 with an investment of Rs. 29 cores to 6,65,124 crores in 2006-07. The bulk of investment was in producing and selling goods in basic industries such as steel, coal, power, petroleum, etc. followed by financial services.

The role of the public sector can be assessed and evaluated in terms of certain key macroeconomic indicators such as national income, employment, saving and investment.

We may now focus on these key indicators:

1. Share of the Public Sector in NDP:

In sixty years of planning, the share of public sector m GDP has improved steadily-from 7.5% in 1950-51 to 21.7% in 2005-06 (at current prices). Thus, public sector accounted for more than one-fourth of India’s GDP. This was due to rapid expansion of the sector. Of late, the share has fallen marginally due to privatisation of a number of public sector enterprises through an act of disinvestments.

2. Employment Generation:

The public sector belongs to the organised segment of the economy. It employees 70% of the workers employed in the organised sector of the Indian economy. In transport and communication, electricity, gas and water and construction, the share of the public sector in employment creation is much higher (about 95%).

3. Contribution to Savings and Capital Formation:

Gross domestic capital formation increased from 10.7% of GNP during the First Plan (1951 -56) to during the Eighth Plan (1992- 97). During this period the share of the public sector improved from 3.5% to 9.2%. However, the share of savings by the public sector in total savings of the country has not undergone a similar change. It increased from 1.7% of GDP during the First Plan to a moderate 3.6% during the Sixth Plan but fell again to 1.4% during the Eighth Plan.

This was due to increased inefficiency of the public sector enterprises and their consequent failure to generate sufficient trading surplus. Another reason for the low rate of saving in the public sector has the growing reliance of the Government on the financial sector to make up the shortfall in resources (i.e., deficit financing). It fell to 1.2% in 2003-04.

According to the new series (with base year 1999-2000), the share of the public sector in gross domestic capital formation increased from 6.9% of GDP in 2001-02 to 7.8% in 2006-07 This is just a marginal improvement. The share of public sector in fixed capital formation at current prices increased from 2.6% in 1950-51 to 6.7% in 1960-61 and to 7% in 2005-06.

Essay # 5. Performance of Public Enterprises:

The performance of public enterprises can be assessed on the basis of their operative efficiency and the consequent financial performance. In this context we may refer to the efficiency of public enterprises. ”

Efficiency:

The efficiency of a PE can best be assessed in terms of its basic objectives. While, the performance of a private enterprise can be evaluated in terms of a single criteria, viz., maximisation of social welfare.

Thus, any attempt to evaluate the performance of PEs, even in financial terms requires a discussion an appropriate efficiency criteria:

1. Efficiency Criteria:

There are two distinct aspects of the financial performance of PEs:

(i) First, PE as an arm of state’ are greatly influenced by the financial policies and exigency of the Government.

(ii) Second, the financial returns of PEs are to be consistent with non-financial objectives such as employment generation, self-reliance, balanced regional development. Some PEs have mixed objectives-partly commercial and partly non-commercial-the realisation of which affect their financial performance.

Another unique aspect of PEs, as from the operational point of view, is that in many cases a one-buyer-one-seller phenomenon arises wherein one Government department is the monopolist buyer and one PE is the monopolist seller. In this case, profit to one PE may represent a loss to the other. This, virtually amounts to cross-subsidization. Thus, private profit cannot be used as a criterion for measuring efficiency of the public sector.

2. Conventional Measures of Efficiency:

The size and magnitude of turnover of many PEs did not increase proportionately with corresponding level of investment. Even at the level of best performance the turnover-investment ratios of PEs are of a standard norm, i.e., three times. Turnover-capital employed ratios also moved in the same way.

The extent of capacity utility fell. Most Central Government PEs were able to utilise less than 50% of their installed capacity per annum (on an average).

Investment per employee also shot up, indicating growing capital intensity. But “a large amount of capital employed was also due to a long gestation period, accretion to capital, and an inefficient quality of the chosen technology, process and products”.

Furthermore, many of the PEs, having been located in backward areas and acting as model employers, had to incur huge expenditures on township construction and maintenance, administration and social overheads.

Central Government PEs earned a net return of only 2.3% of capital employed during 1971- 72 and 1990-91. However, the Planning Commission feels that the Central Government’s non- departmental enterprises should aim at earning 10% per annum.

This is quite consistent with the Government’s decision to fix 10-15% (net of taxes) as a fair return in determining administered prices. The net profit after tax to capital employed in the public sector has 1.1 % in 1980- 81. It was 2.3% in 1990-91, 6.7% in 2001-02 and 12.3% in 2006-07.

3. Total Productivity:

The efficiency of PEs can be increased in terms of total productivity. With rising capital intensity (due to increasing ICOR), labour productivity has risen faster but capital productivity has fallen. The combined effect of these has been slow growth of productivity.

Essay # 6. Constraints on Performance of Public Enterprises:

The poor performance of PEs is attributed to several constraints. The main factors inhibiting their operation were:

1. Idle Capacity:

The range of un-utilised capacity in PEs has been 35-50%. The main reasons for this are power shortage, fluctuations and failures, adverse industrial relations situation, lack of balancing equipment, equipment breakdown, inadequacy of demand, inadequacy or poor quality of raw materials, design deficiency, etc.

These factors were interrelated. Industrial unrest was related to the overall working conditions that prevailed in PEs. The availability of balancing equipment might depend on the access to scarce resources like foreign exchange. The other factors are related to management of PEs. The managerial constraint has to be treated separately.

2. Organisation and Management of PEs:

The poor performance of PEs is no less due to the bureaucratic structure and rigid form of management. From the very beginning the Government had adopted a bureaucratic structure and form of management for PEs. And the only thing that saves us from the bureaucracy is its inefficiency.

The top-level bureaucratic elements often prevented spread of professionalism in PEs. Moreover, due to frequent political interference at the highest level, there has occurred brain drain from the public to the private sector.

It was not the other way government. As Ronald Reagn has put it, “The best minds are not in government. If they were, business would hire them away”. For these reasons controversy has arisen concerning autonomy of the management of PEs in relation to Government control.

3. Interference with Commercial Freedom and Problems of Coordination:

The adverse effect of Government control is reflected in the abnormal delays in sanctioning projects. The procedural delays lead to delay in decision-making. The end result is delay in project implementation and cost escalation. People at the secretariat level of PEs have failed to understand the fundamental difference between administrative and industrial management.

They failed to understand that “industrial management, contracted with problems of production, changes in technology operational bottlenecks, varying market conditions, and uneven flow of essential inputs requires speedy decision-making”.

Another important type of Government control has been the enforcement of pricing policy, having no relation to the economic viability of the units As late as in 1971 the Bureau of Public Enterprises took decision on price preference for PEs for the Government and other public sector purchases. Moreover, till date, inter-sectoral price balance has not been worked out.

Furthermore, “a solution to the problem of determining priorities in the allocation of various facilities (apart from finance to the PEs) depends on coordination among public sector enterprises between enterprises and the Government and also between the enterprises and the state’s departmental undertakings. With the rapid expansion and diversification of the public sector the problem of coordination has assumed serious proportions. More and more, output of one undertaking has become dependent on the inputs from other undertakings. In such circumstances lack of coordination has an adverse effect on the rest of the economy.”

The present power crisis is due to non-availability (or lack of timely availability) of adequate coal. This is due to shortage of wagons.

In spite of the existence of a few coordinating agencies major coordination problems arise due to the lack of a clear public sector philosophy and coherence of objectives of different undertakings. The rigid administrative structure has also led to lack of coordination within the enterprises by obstructing the flow of information and creating parriers to two-way communication.

4. Employment Practices:

There is surplus staff in a large number of PEs, including the Indian railways, steel plants, fertiliser plants, and chemical plants. This offsetting is due to top- heavy administration on the one hand and lack of proper manpower planning on the other

5. Pacing Policy:

Relatively low prices of many products and services of PEs amounted to indicate subsidisation. Certain enterprises were directed or persuaded to operate on a lower than possible price on non-economic (mainly socio-political) considerations. In this context we may cite the examples of steel prices, bus fares, postal charges, electricity tariffs, etc.

6. Generation and Utilisation of Surpluses:

Most PEs incurred losses. Some have made profits, particularly in the oil sector. However, low surplus generation led to corresponding low rate of utilisation of internal surplus for the expansion of self-financing schemes.

7. Labour-Management (Industrial) Relations:

The salary differential between the skilled workers and management in PEs is not wide. But the gap in earnings (wages and compensation) between the semi-skilled and unskilled employees is quite large. In fact, the condition of unskilled workers is more or less the same as in the private sector.

8. Access to Scarce Resources:

The performance of many PEs has been hampered by lack of access to appropriate technology. Due to technological gap, many PEs had to depend on foreign technology. This has increased India’s technological dependence on multinational corporations under unfavourable terms and conditions. The end result was import of inappropriate technology—both in terms of product use and factor use.

Essay # 7. Concluding Remarks to Public Enterprises:

The overall evaluation of the working of PEs essentially relates to the pre-Reform period (1951- 1991) Over these years, PEs were supposed to reach the commanding heights of the economy.

The PEs were treated as an instrument for achieving various goals, which were often conflicting in nature viz:

(i) To allocate scarce investible resources to the desired directions—sectors and regions;

(ii) To stabilise prices;

(iii) To generate more surplus for future investment;

(iv) To stimulate R-and-D for technology development, assimilation, and absorption. But the sad truth is that none of the above objectives has been realised to a significant extent over the first tour decades of planning.

Due to poor performance of PEs the Government has changed its perception of the role of PEs as an instrument of policy. particularly in the period of economic liberalisation or the new policy region (since July 1991). It is felt that “in the new regime, with greater reliance on market forces, the thrust has been on restricting the entire set of public sector enterprises including privatisation.

The move is intended to make the existing PEs financially more viable and even profit-making and to restrict the future role of PEs in areas of market failure. The new policy direction would inevitably lead to several operational problems and also raise some analytical issues.

Essay # 8. New Policy towards the Public Sector:

The present Industrial Policy (1991) provides a new approach to public enterprise. The stress is on measures to be taken to make these enterprises more growth-oriented and technologically sound programmes.

Certain priority areas for growth of public enterprises in the future have been identified such as:

(i) Essential infrastructure goods and resources;

(ii) Technology development and building of manufacturing capabilities in areas which are crucial for the long- term development of the economy and where not much private investment is being made, and

(iii) Manufacture of strategic products such as defence equipment.

The development of future strategy will be to strengthen those PEs which are in the reserved areas of operation, or ones in high priority areas, or are generating adequate profits (a major portion of which can be reinvested). The plan is to provide such enterprises a much greater degree of management autonomy through the system of memoranda of undertaking.

The Government will also seek to promote competition in high priority and even reserved areas for private sector participation. In case of certain selected enterprises, a portion of Government holdings in the equity share of these enterprises will be disinvested. The main objective is to impose adequate market discipline on the performance of PEs through control of monopolies, and prohibition of monopolistic and restrictive and unfair trade practices.

These will provide review of the portfolio of public sector investments with a view to focussing the role of public sector in areas of high technology and essential infrastructures which are of strategic significance for the country’s economy. No doubt some reservation for the public sector will be retained. But certain areas which were exclusively reserved for the public sector will be opened up to the private sector—on a selective basis though.

Public enterprises which are chronically sick and which cannot be revived will be referred to the Board for Industrial and Financial Restructuring (BIFR), earlier called Board of Industrial and Financial Reconstruction, or other similar high level institution for the formulation of revival/ rehabilitation schemes. And, in order to protect the interest of workers, Boards of Public Sector companies would be made more professional and given greater autonomy.

There will be more stress on improvement of performance of public enterprises through the memorandum of undertaking (MOU). Though, this management would be granted greater autonomy (i.e., given more power) and will be held accountable. In order to make MOU negotiations and implementing the same more effectives, the technical expertise on the part of the Government would be upgraded.

In short, the Government’s policy toward the public sector will be based on judicious way of three things:

(i) Strengthening strategic units,

(ii) Privatizing non-strategic ones through gradual disinvestments or strategic scale, and

(iii) Devising viable rehabilitation strategy for weak units

Four man elements of GOI’s policy toward PSUs are:

1. Bringing down Government equity in all non – strategic PSUs to 26% or lower, if necessary;

2. Restructure and revive potentially viable PSUs;

3. Close down PSUs which stand no chance of revival; and

4. Fully protecting the interest of workers.

In order to ensure smooth disinvestments of some PSUs as per Plan priorities and targets a new Department of Disinvestment has been set up. The Department is responsible for all matters related to disinvestments of Central Government equity in Central Public Sector undertakings implementation of disinvestments decisions and recommendations of the erstwhile Disinvestment.