In this essay we will discuss about welfare economics. After reading this essay you will also learn about:- 1. Objectives of Welfare Economics 2. The Nature of Welfare Economics 3. Pareto Optimality 4. Implications 5. Limitations.

Economics has two major aspects: positive (descriptive-analytical) aspect and normative (welfare) aspect. Positive economics is concerned with the description and analysis of the working of the economic system.

Welfare economics, on the other hand, is concerned with the appraisal and evaluation of states of the economy or methods of organising the economic system, i.e., it is concerned with whether an economic system produces ‘good’ results as well as with determining what those results are and how they are achieved.

The fundamental distinction between positive economics and welfare assumptions as well as its conclusions, at least under ideal circumstances, can be subjected to empirical and/or logical tests to determine their truth or falsity, maximisers. The basic assumptions underlying welfare economics, on the other hand, are value judgments that any economist is free to accept or reject; there is no conceivable manner in which the truth or falsity of these axioms could be tested.

Welfare economics is scientific only in so far as its conclusions are based upon the results of positive economics; thus, given value judgments sufficient to define what is meant by a ‘desirable’ state of the economy, positive economics can be employed to determine whether such a state can be reached with our existing economy system.

The conclusion of such an analysis may then be subjected to the same tests for truth or falsity as those employed in other aspects of positive economics. In short, whereas positive economics adopts purely scientific approach, welfare economics involves an ethical approach to the study of economics. The distinction is largely based on the distinction between is and ought, between objective and subjective issues. Welfare economics is much concerned with policy and value judgements.

Welfare economics achieved distinction of a separate discipline only after the publication of A. C. Pigou’s. The economics of Welfare (1920). He emphasised maximum social welfare as a goal towards which the science of economics should strive.

Objectives of Welfare Economics:

The objective of welfare economics is the evaluation of the social desirability of alternative economic states. An economic state is a particular arrangement of economic activities and of the resources of the economy. Each state is characterised by a different allocation of resources and a different distribution of the rewards for economic activity.

The economist attempts to prescribe a method by which one state of the economy can be transformed into another. Again, policy measures are often available for changing an existing situation. What is important to know in such cases is whether the contemplated change is desirable. Assume that the economy can attain multi-market (general) equilibrium at two different sets of commodity and factor prices.

Since the desires of consumers and entrepreneurs are simultaneously satisfied at both equilibria, society cannot choose between them, if at all, only on welfare grounds. The principles by which such problem might be solved fall within the subject matter and scope of welfare economics.

The Nature of Welfare Economics:

Welfare economics differs from traditional microeconomics, being concerned with the extent to which the objectives of the society as a whole are fulfilled rather than the private objectives of its members. It focuses on those pressing problems concerning the appropriate policy of the society which are left unanswered by traditional economics.

The effect of government policy may be beneficial to some individuals and harmful to others. Traditional economics is not fully equipped to assess whether on balance it is a desirable policy. Thus, there are conflicts of private interests.

Two-fold Role:

The role of welfare economics is two-fold to pinpoint the issues about which value judgments as to the objectives of the society must be made; and to reasons from those objectives, whatsoever they may be, the conclusions as to the appropriateness of particular policies as means of achieving them.

One cannot assess the appropriateness of a particular policy, nor choose among alternative policies, unless one pays attention both to the probable consequences of those policies and the objectives that are sought. Welfare economics is concerned with the methodology of such assessments.

Microeconomic analysis has developed the theories of production, costs, consumer behaviour and markets in an effort to enable us to infer what the relevant forces are and what changes in them can be expected to ensue from given policies. Welfare economics, similarly, attempts to unravel the objective side of the problem.

The welfare of a society depends, in the broadest sense, upon the satisfaction levels of all its consumers. Such statements are based on ethical belief or value judgments and cannot be proved. But almost every alternative to be judged by welfare economists will have favourable effects on some people and unfavourable effects on others.

In light of this, the economist has two choices. He may decline to deal with cases in which proposed social change improves the lot of some and deteriorates the lot of others and content himself with realising situations in which unambiguous welfare improvements are possible. Alternatively, he may decide to make interpersonal comparisons of utility and analyse a broader class of situations.

In the former case, he is primarily concerned with efficient allocation of resources. In the latter, he must make explicit value judgments. In principle, “one would hope that these will rest on a social consensus, since the economist has no more competence than anyone else to say that a particular move is desirable if it has unfavourable effects upon some members of society.”

Pareto Optimality:

Most economic analysis is concerned with the welfare aspects of economic activity—how to achieve maximum social welfare, i.e., the state of well-being of all the persons comprising an economic system. Welfare economics is concerned with the evaluation of alternative economic states or situations from the point of view of the society’s well-being. Normative economists are always trying to think of ways for the economy to achieve an optimal economic state, that is, a state which would enable society to attain the maximum possible social welfare.

Since it is most difficult to measure ‘social welfare’ for group of individuals (because it involves interpersonal comparisons and calls for value judgment), the economists use the Pareto optimality criterion for deciding whether the social welfare is higher in one economic situation than in another.

According to the Pareto optimality criterion, any change that makes at least one individual better off and no one worse off is a decrease in social welfare. A situation (state, or configuration) in which it is impossible to make anyone better off without making someone worse off is said to be Pareto optimal or efficient.

For Pareto optimality to exist in an economic system three conditions must be met:

1. The distribution of output must be such that the marginal rate of substitution for one product for any other product is the same for all consumers.

2. The allocation of resources must be such that the marginal rate of technical substitution of any one resource for any other resource is the same in the production of all products for which these resources can be used.

3. The distribution of output among consumers must be such that the marginal rate of substitution of any one product is equal to the marginal rate of transformation of the products.

The Pareto Criterion simply holds that, if a change makes at least one person better off and no one else worse off it produces an improvement in social welfare. However, it is assumed that each party is able to evaluate his own loss or gain to the best of his ability and to convey this information to the decision making authority.

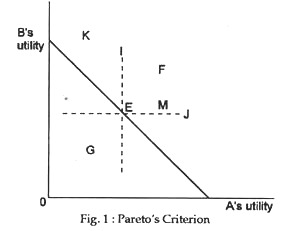

Consider Fig. 1. Here, the line CD is known as the utility possibility curve. Here individual A’s utility is measured on the horizontal axis and B’s on the vertical axis. The line CD shows the different combinations of their utilities associated with various distributions of some given amount of resources. Assuming that A is not concerned with B’s wishes, he prefers point D to all others along CD; similarly, B prefers points closest to C.

From a given endowment at point E, an economic change causing a movement to some point F above and to the right of point E is an unambiguous improvement for both. Similarly, any change in a movement to some point G below and to the left of point E would be rejected on welfare grounds.

Again, changes causing a movement to points H and I would also be adopted, since one person gains but the other does not lose. On the contrary, changes causing movements to points 1 and line CD point K would be rejected, since one or the other is made worse off.

Perfect Competition and Pareto Optimality:

Pareto optimality provides a definition of the economic efficiency of allocations (of resources and commodities) that serves as the basis for much of welfare economics. An allocation is Pareto-optimal or Pareto-efficient if production and distribution cannot be reorganised to increase the utility of one or others.

Under perfect competition, where all prices are equal to their marginal costs, when all factor-prices are equal to values of marginal-products and all total costs are minimised, where the genuine desires and well-beings of individuals are represented by their utilities as expressed by their rupee voting, then the resulting equilibrium has the efficiency property that “you can’t make any one person better off without hurting some other person”. Thus, perfect competition implies Pareto-optimality.

Implications of Welfare Economics:

An important implication of welfare economics is that, the existing free enterprise institutions are to be kept alive, motivated and used so as to secure maximum social welfare. True enough, the western countries as well as Japan are welfare states inasmuch as their economic systems consciously work to remove poverty, though nothing tangible has been done to abolish inequalities of income and wealth.

These economies have attempted to ensure full employment and, if a person is out of job, he is given sufficient relief. Government welfare expenditure transfers purchasing power to the needy and worthy without regard to their providing current service in exchange. Payments are made to the unemployed, freedom fighters, pensioned workers and needy families (refugees), and to old and the handicapped. Because of such payments the modern mixed economy is called the ‘welfare state’.

Welfare economies seeks to put the economic laws to use to see that not only the size of the national cake increases to the maximum possible extent but also that the distribution of the cake is such as to bring about the maximum satisfaction to the maximum number of people.

This implies maximum production of economic goods and services and their equitable distribution. India is also trying to be a welfare state and sometime ago the government promised to ensure full employment within a decade by means of, amongst others, rural development and development of labour- intensive industries. The trend in India is towards a socialist pattern of society.

We noted that welfare economics has assumed considerable importance for a two-fold reasons:

(1) Emergence of the concept of welfare state, and

(2) The role which state plays in the process of economic development.

Many of the ideas of welfare economics are being used, especially optimum utilisation of resources from a social angle and the process of income and wealth transfer, with the object of maximising social welfare. According to Pigou and other neo-classical economists this process of shift has to go on till the marginal utility of the last unit of money transferred from the rich to the poor is rendered equal.

The emphasis has shifted from GNP to gross national welfare and the review of economic activity from the angle of social cost and benefit. This is also symptomized by the expansion of public enterprises whose objective is maximisation of social welfare. Even some modern companies have attempted to discharge their social responsibilities.

Limitations of Welfare Economics:

It should be stressed that welfare economics, although useful, is certainly no panacea. By itself, welfare economics can seldom provide a clear-cut solution to issues of public policy. Perhaps the most serious limitation of welfare economics stems from the fact that there is no scientific way to compare the utility levels of different individuals. So, the question of whether one distribution of income is better than another must be settled on ethical and not scientific grounds.