In this essay we will discuss about Inflation. After reading this essay you will learn about:- 1. Meaning of Inflation 2. Demand-Pull Inflation 3. Cost-Push Inflation 4. Mixed Demand-Pull Cost-Push Inflation 5. Sectoral or Demand-Shift Inflation 6. Structural Inflation 7. Mark-Up Inflation 8. Causes 9. Effects 10. Costs 11. Measures to Control Inflation.

Contents:

- Essay on the Meaning of Inflation

- Essay on Demand-Pull Inflation

- Essay on the Cost-Push Inflation

- Essay on the Mixed Demand-Pull Cost-Push Inflation

- Essay on the Sectoral or Demand-Shift Inflation

- Essay on the Structural Inflation

- Essay on the Mark-Up Inflation

- Essay on the Causes of Inflation

- Essay on the Effects of Inflation

- Essay on the Costs of Inflation

- Essay on the Measures to Control Inflation

1. Essay on the Meaning of Inflation:

To the neo-classicals and their followers at the University of Chicago, inflation is fundamentally a monetary phenomenon. In the words of Friedman, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon…and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than output.”

But economists do not agree that money supply alone is the cause of inflation. As pointed out by Hicks, “Our present troubles are not of a monetary character.” Economists, therefore, define inflation in terms of a continuous rise in prices. Johnson defines “inflation as a sustained rise” in prices.

Brooman defines it as “a continuing increase in the general price level.” Shapiro also defines inflation in a similar vein “as a persistent and appreciable rise in the general level of prices.” Dernberg and McDougall are more explicit when they write that “the term usually refers to a continuing rise in prices as measured by an index such as the consumer price index (CPI) or by the implicit price deflator for gross national product.”

However, it is essential to understand that a sustained rise in prices may be of various magnitudes. Accordingly, different names have been given to inflation depending upon the rate of rise in prices.

1. Creeping Inflation:

When the rise in prices is very slow like that of a snail or creeper, it is called creeping inflation. In terms of speed, a sustained rise in prices of annual increase of less than 3 per cent per annum is characterised as creeping inflation. Such an increase in prices is regarded safe and essential for economic growth.

2. Walking or Trotting Inflation:

When prices rise moderately and the annual inflation rate is a single digit. In other words, the rate of rise in prices is in the intermediate range of 3 to 7 per cent annum or less than 10 per cent. Inflation at this rate is a warning signal for the government to control it before it turns into running inflation.

3. Running Inflation:

When prices rise rapidly like the running of a horse at a rate of speed of 10 to 20 per cent per annum, it is called running inflation. Such an Inflation affects the poor and middle classes adversely. Its control requires strong monetary and fiscal measures, otherwise it leads to hyperinflation.

4. Hyperinflation:

When prices rise very fast at double or triple digit rates from more than 20 to 100 per cent per annum or more, it is usually called runaway or galloping inflation. It is also characterised as hyperinflation by certain economists.

In reality, hyperinflation is a situation when the rate of inflation becomes immeasurable and absolutely uncontrollable. Prices rise many times every day. Such a situation brings a total collapse of monetary system because of the continuous fall in the purchasing power of money.

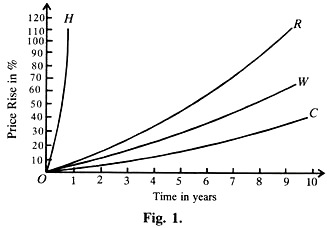

The speed with which prices tend to rise is illustrated in Figure 1. The curve C shows creeping inflation when within a period of ten years the price level has been shown to have risen by about 30 per cent. The curve W depicts walking inflation when the price rose by more than 50 per cent during ten years. The curve R illustrates running inflation showing a rise of about 100 per cent in ten years. The steep curve H shows the path of hyperinflation when prices rose by more than 120 per cent in less than one year.

2. Essay on the Demand-Pull Inflation:

Demand-pull inflation or excess demand inflation is the traditional and most common type of inflation. It takes place when aggregate demand is rising while the available supply of goods is becoming less. Goods may be in short supply either because resources are fully utilised or production cannot be increased rapidly to meet the increasing demand. As a result, prices begin to rise in response to a situation often described as “too much money chasing too few goods.”

There are two principal theories about the demand-pull inflation that of the monetarists and the Keynesians. We shall also discuss a third one propounded by the Danish economist, Bent Hansen.

1. Monetarist View or Monetary Theory of Inflation:

The monetarists emphasise the role of money as the principal cause of demand-pull inflation. They contend that inflation is always a monetary phenomenon. Its earliest explanation is to be found in the simple quantity theory of money. The monetarists employ the familiar identity of Fisher’s Equation of Exchange.

MV = PQ

where M is the money supply, V is the velocity of money, P is the price level, and Q is the level of real output.

Assuming V and Q as constant, the price level (P) varies proportionately with the supply of money (M). With flexible wages, the economy was believed to operate at full employment level. The labour force, the capital stock, and technology also changed only slowly over time.

Consequently, the amount of money spent did not affect the level of real output so that a doubling of the quantity of money would result simply in doubling the price level. Until prices had risen by this proportion, individuals and firms would have excess cash which they would spend, leading to rise in prices.

So inflation proceeds at the same rate at which the money supply expands. In this analysis the aggregate supply is assumed to be fixed and there is always full employment in the economy. Naturally, when the money supply increases it creates more demand for goods but the supply of goods cannot be increased due to the full employment of resources. This leads to rise in prices. But it is a continuous and prolonged rise in the money supply that will lead to true inflation.

Friedman’s View:

Modern quantity theorists led by Friedman hold that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon that arises from a more rapid expansion in the quantity of money than in total output.” He argues that changes in the quantity of money will work through to cause changes in nominal income.

Inflation everywhere is based on an increased demand for goods and services as people try to spend their cash balances. Since the demand for money is fairly stable, this excess spending is the outcome of a rise in the nominal quantity of money supplied to the economy. So inflation is always a monetary phenomenon.

Next Friedman discusses whether an increase in money supply will go first into output or prices. Initially, when there is monetary expansion, the nominal income of the people increases. Its immediate effect will be to increase the demand for labour. Workers will settle for higher wages. Input costs and prices will rise. Profit margins will be reduced and the prices of products will increase.

In the beginning, people do not expect prices to continue rising. They regard the price rise as temporary and expect prices to fall later on. Consequently, they tend to increase their money holdings and the price rise is less than the rise in nominal money supply. Gradually people tend to readjust their money holdings. Price then rise more than in proportion to the money supply.

The precise rate at which prices rise for a given rate of increase in the money supply depends on such factors as past price behaviour, current changes in the structure of labour, product markets and fiscal policy. Thus, according to Friedman, the monetary expansion works through output before inflation starts.

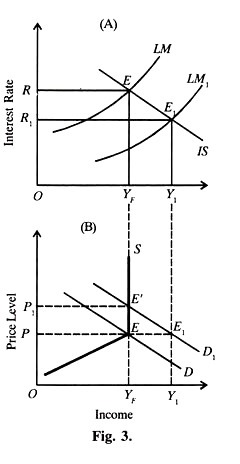

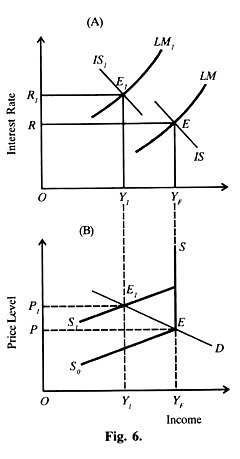

The quantity theory version of the demand-pull inflation is illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 3 (A) & (B). Suppose the money supply is increased at a given price level P as determined by D and S curves in Panel (B) of the figure. The initial full employment situation at this price level is shown by the intersection of IS and LM curves at E in Panel (A) of the figure where R is the interest rate and YF is the full employment level of income.

Now with the increase in the quantity of money, the LM curve shifts rightward to EM, and intersects the IS curve at E1 such that the equilibrium level of income rises to Y, and the rate of interest is lowered to R1 As the aggregate supply is assumed fixed, there is no change in the position of the IS curve.

Consequently, the aggregate demand rises which shifts the D curve to the right to D1 and thus excess demand is created equivalent to EE1(=YFY1) in Panel (B) of the figure. This raises the price level, the aggregate supply being fixed, as shown by the vertical portion of the supply curve S.

The rise in the price level reduces the real value of the money supply so that the LM, curve shifts to the left to LM. Excess demand will not be eliminated until aggregate demand curve D, cuts the aggregate supply curve S at E’.

This means a higher price level P1in Panel (B) and return to the original equilibrium position E in the upper Panel of the figure where the IS curve cuts the LM curve. The “result, then is self-limiting, and the price level rises in exact proportion to the real value of the money supply to its original value.”

2. Keynes’ Theory of Demand-Pull Inflation:

Keynes and his followers emphasise the increase in aggregate demand as the source of demand-pull inflation. There may be more than one source of demand. Consumers want more goods and services for consumption purposes. Businessmen want more inputs for investment. Government demands more goods and services to meet civil and military requirements of the country. Thus the aggregate demand comprises consumption, investment and government expenditures.

When the value of aggregate demand exceeds the value of aggregate supply at the full employment level, the inflationary gap arises. The larger the gap between aggregate demand and aggregate supply, the more rapid the inflation.

Given a constant average propensity to save, rising money incomes at the full employment level would lead to an excess of aggregate demand over aggregate supply and to a consequent inflationary gap. Thus Keynes used the notion of the inflationary gap to show an inflationary rise in prices.

The Keynesian theory is based on a short-run analysis in which prices are assumed to be fixed. In fact, prices are determined by non-monetary forces. On the other hand, output is assumed to be more variable which is determined largely by changes in investment spending. The Keynesian chain of causation between changes in nominal money income and in prices is an indirect one through the rate of interest. When the quantity of money increases, its first effect is on the rate of interest which tends to fall.

A fall in the interest rate would, in turn, increase investment which would raise aggregate demand. A rise in aggregate demand would first affect only output and not prices so long as there are unemployed resources. But a sudden large increase in the aggregate demand would encounter bottlenecks when resources are still unemployed. The supply of some factors might become inelastic or others might be in short supply and non-substitutable.

This would lead to increase in marginal costs and hence in prices. Accordingly prices would rise above average unit cost and profits would increase rapidly which, in turn, would bid up wages owing to trade union pressures. Diminishing returns might also set in some industries.

As full employment in reached, the elasticity of supply of output falls to zero and prices rise without any increase in output. Any further increase in expenditure would lead to excess demand and to more than proportional increase in prices. Thus, in the Keynesian view so long as there in unemployment, all the change in income is in output, and once there is full employment, all is in prices.

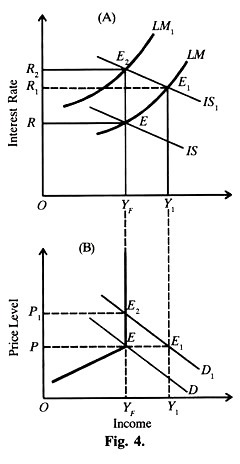

The Keynesian theory of demand-pull inflation is explained diagrammatically in Figure 4 (A) and (B). Suppose the economy is in equilibrium at E where the IS and LM curves intersect with full employment income level YF and interest rate R, as shown in Panel (A) of the figure.

Corresponding to this situation, the price level is P in Panel (B). Now the government increases its expenditure. This shifts the IS curve rightward to IS1 and intersects the LM curve at E1 when the level of income and the interest rate rise to Y, and R1respectively. The increase in government expenditure implies an increase in aggregate demand which is shown by the upward shift of the D curve to D1 in the lower Panel (B) of the figure.

This creates excess demand to the extent of EE, (=YFY1) at the initial price level P. Excess demand tends to raise the price level, as aggregate supply of output cannot be increased after the full employment level. As the price level rises, the real value of money supply p-falls. This shifts the LM curve to the left to LM, such that it cuts the ZS, curve at E2 where equilibrium is established at the full employment level of income YF but at a higher interest rate R2 (in Panel A) and a higher price level P1 (in Panel B). Thus the excess demand caused by the rise in government expenditure eliminates itself by changes in the real value of money.

3. Bent Hansen’s Excess Demand Model:

The Danish economist Bent Hansen has presented an explicit dynamic excess demand model of inflation which incorporates two separate price levels, one for the goods market and other for the factor (labour) market.

Its Assumptions:

His dynamic model for demand inflation is based on the following assumptions:

1. There is perfect competition in both the goods market and the factor market.

2. Price at the moment will persist in the future.

3. Only one commodity is produced with the help of only one variable factor, labour services.

4. The quantity of labour services per unit of time is a given magnitude.

5. There is a fixed actual level of employment and consequently of output which is full employment.

The Model:

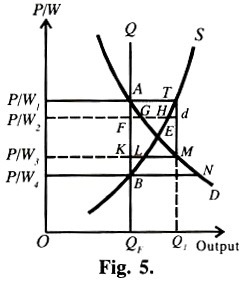

Given these assumptions, the model is explained in terms of Figure 6. The vertical axis measures the price-wage ratio P/W (inverse of the real wage). The aggregate real income or output is measured along the horizontal axis. S is the supply curve of planned production, S=F (P/ W).

It varies positively with P/W such that the higher the price is relative to the wage rate, the less is the demand for consumer goods, D=F(P/W). D is the demand curve of planned demand which has an inverse relationship with P/W such that the higher price is relative to the wage rate the larger is the planned production. The vertical line Q is the full employment output level QF and Q=constant.

The horizontal difference between the curve D and Q is the “quantitative inflationary gap in the goods markets”. Such a gap exists at all price-wage ratios below (P/W) in the figure. The horizontal difference between the curves S and Q is the index for the factor-gap.” Thus (D-Q) is the goods gap and (S-Q) is the factor gap.

Suppose the two curves D and S intersect to the right of the full employment level of output at point E. This happens if there is monetary pressure of inflation because otherwise it would not be possible with given P/W to have a positive inflationary gap in the goods markets and positive factor-gap simultaneously. A monetary pressure of inflation exists only when P/W is between P/W1and P/W4. When P/W>P/W, the inflationary gap in the goods-market is greater than zero; and when P/W<P/W4 both the index for the factor- gap and the factor-gap are negative.

Next Hansen introduces two dynamical equations:

dp/dt =F(D-Q) …(1)

dw/dt = F (S-Q) …(2)

where dp/dt is the speed of the rise in the price level, and dw/dt is the speed of the rise in the wage rate.

When (D-Q) is zero, dp/dt = 0; and when (S-Q) is zero, dw/dt = O. This is a static equilibrium system. When the two gaps are positive, the rates of price and wage changes are also positive.

It follows that when both the excess demand for goods (D-Q) and the excess demand for factors (S-Q) are positive, both price and wage-rate will rise. Each will be a quasi-equilibrium position which is stable in the sense that whatever price-wage relation is started, there will be forces at work which tend to bring the system back to the quasi-equilibrium position.

The quasi-equilibrium system is given by

Q = Constant S = F (P/W) D=f (P/W)

and P/W f(D-Q)/F (S-Q)

Let us take the figure where the curves S and D intersect at point E, to the right of the full employment level of output QF. Since point E cannot be achieved, an initial unstable equilibrium occurs at point A where the price-wage ratio is (P/W1). In this situation, there is no goods gap and goods prices do not rise because planned demand (D) equals full employment output (QF) at A. But there is a large factor gap at point T so that wages rise rapidly.

This is because planned production Q1 exceeds the full employment output QF at (P/W,). But this is not possible because Q1 output is more than the full employment output QF. Consequently, there is excess demand for labour which leads to labour shortages and to rise in the wage rate. Thus P/W falls. When the price-wage ratio falls, an excess demand for goods (goods gap) begins to appear and that for factors (factor gap) simultaneously decreases. Suppose P/W, falls to P/ W2. At P/W2, the goods gap FG is smaller than the factor gap FH which means that the small goods gap produces a slow rise in prices and the larger factor gap produces a higher rise in wage rate.

This will lead to a further fall in wage-price ratio to P / W3. At P/ W3, the factor gap is reduced to KL and the goods gap is raised to KM, thereby leading to a slower rise in wage rate and more rapid rise in prices respectively. This retards the fall in the wage-price ratio. In this way, the price-wage ratio will fall, increasing slowly to a level where the goods gap corresponds to the factor gap.

This means that the percentage rise of wage rate per unit time is equal to the percentage rise of the price per unit time. Similar reasoning will apply if we start from P/W4 where the large goods gap BN and zero factor gap would raise prices and hence the wage-price ratio. A key determinant of the level of price-wage ratio is the flexibility of wage-rate and prices relative to each other. The more flexible are prices relative to wages, the closer is the value of price-wage ratio to P/W4.

Between P/W1 and P/W4, there is some quasi-equilibrium at which both prices and wage-rates move together. The quasi-equilibrium is not a static equilibrium but a dynamic one, since both prices and wage rates rise without interruption and the relevant gaps are not zero.

“The actual speed of the inflation to quasi- equilibrium will depend on the absolute sensitivity of wage and price change to the size of the relevant gaps. If both are relatively volatile, inflation will be rapid; if both are relatively sluggish, inflation will be slower.” The more rigid prices are relative to wages, the closer is the value of price-wage ratio to P/W4.

To conclude, Hensen’s excess demand model of inflation points toward the sources of inflationary pressures and the actual process of inflation in the economy. But, according to Ackley, it fails to specify the rate at which inflation will occur. It is an elegant but perhaps rather empty analysis of demand inflation.

3. Essay on the Cost-Push Inflation:

Cost-push inflation is caused by wage increases enforced by unions and profit increases by employers. The type of inflation has not been a new phenomenon and was found even during the medieval period. But it was revived in the 1950s and again in the 1970s as the principal cause of inflation. It also came to be known as the “New Inflation.” Cost-push inflation is caused by wage-push and profit-push to prices.

The basic cause of cost-push inflation is the rise in money wages more rapidly than the productivity of labour. In advanced countries, trade unions are very powerful. They press employers to grant wage increases considerably in excess of increases in the productivity of labour, thereby raising the cost of production of commodities. Employers, in turn, raise prices of their products. Higher wages enable workers to buy as much as before, in spite of higher prices. On the other hand, the increase in prices induces unions to demand still higher wages. In this way, the wage-cost spiral continues, thereby leading to cost-push or wage-push inflation.

Cost-push inflation may be further aggravated by upward adjustment of wages to compensate for rise in the cost of living index. This is usually done in either of the two ways.

First, unions include an “escalator clause” in contracts with employers, whereby money wage rates are adjusted upward each time the cost of living index increases by some specified number of percentage points.

Second, in case where union contracts do not have an escalator clause, the cost of living index is used as the basis for negotiating larger wage increases at the time of fresh contract settlements.

Again, a few sectors of the economy may be affected by money wage increases and prices of their products may be rising. In many cases, their products are used as inputs for the production of commodities in other sectors. As a result, production costs of other sectors will rise and thereby push up the prices of their products. Thus wage-push inflation in a few sectors of the economy may soon lead to inflationary rise in prices in the entire economy.

Further, an increase in the price of domestically produced or imported raw materials may lead to cost-push inflation. Since raw materials are used as inputs by the manufacturers of finished goods, they enter into the cost of production of the latter. Thus a continuous rise in the prices of raw materials tends to set off a cost-price-wage spiral.

Another cause of cost-push inflation is profit-push inflation. Oligopolist and monopolist firms raise the prices of their products to offset the rise in labour and production costs so as to earn higher profits. There being imperfect competition in the case of such firms, they are able to “administer prices” of their products.

“In an economy in which so called administered prices abound, there is at least the possibility that these prices may be administered upward faster than costs in an attempt to earn greater profits. To the extent such a process is widespread profit-push inflation will result.” Profit-push inflation is, therefore, also called administered-price theory of inflation or price-push inflation or sellers’ inflation or market-power inflation. But there are certain limitations on the power of firms to raise their profits. They cannot raise their selling prices to increase their profit-margins if the demand for their products is stable. Moreover, firms are reluctant to increase their profits every time unions are successful in raising wages.

This is because profits of a firm depend not only on price but on sales and unit costs as well, and the latter depend in part on prices charged. So firms cannot raise their profits because their motives are different from unions.

Lastly, profits form only a small fraction of the price of the product and a once- for-all increase in profits is not likely to have much impact on prices. Economists, therefore, do not give much importance to profit-push inflation as an explanation of cost- push inflation.

Cost-push inflation is illustrated in Figure 6 (A) and (B). First consider Panel (B) of the figure where the supply curves So S and S1S are shown as increasing functions of the price level up to full employment level of income YF. Given the demand conditions as represented by the demand curve D, the supply curve So is shown to shift to S, in response to cost-increasing pressures of oligopolies, unions, etc. as a result of rise in money wages. Consequently, the equilibrium position shifts from E to E1 reflecting rise in the price level from P to P1 and fall in output, employment and income from YF to Y1 level.

Now consider the upper Panel (A) of the figure. As the price level rises, the LM curve shifts to the left to LM, because with the increase in the price level to P, the real value of the money supply falls. Similarly, the IS

curve shifts to the left to IS, because with the increase in the price level, the demand for consumer goods falls due to the Pigou effect. Accordingly, the equilibrium position of the economy from E to E1 where the interest rate increases from R to R, and the output, employment and income levels fall from the full employment level of YF to Y1.

Its Criticisms:

The cost-push theory has been criticised on three issues.

First, cost-push inflation is associated with unemployment. So the monetary authority is in a fix because to control inflation it will have to tolerate unemployment.

Second, if the government is committed to a policy of full employment, it will have to tolerate wage increases by unions, and hence inflation.

Lastly, if the government tries to increase aggregate demand during periods of unemployment, it may lead to increase in wages by trade union action instead of raising output and employment.

4. Essay on the Mixed Demand-Pull Cost-Push Inflation:

Some economists do not accept this dichotomy that inflation is either demand-pull or cost-push. They hold that the actual inflationary process contains some elements of both. In fact, excess demand and cost-push forces operate simultaneously and interdependently in an inflationary process.

Thus inflation is mixed demand-pull and cost-push when price level changes reflect upward shifts in both aggregate demand and supply functions. But it does not mean that both demand-pull and cost-push inflations may start simultaneously.

In fact, an inflationary process may begin with either excess demand or wage-push. The timing in each case may be different. In demand-pull inflation, price increases may precede wage increases, while it may be the other way round in the case of cost-push inflation. So price increases may start with either of the two forces, but the inflationary process cannot be sustained in the absence of the other forces.

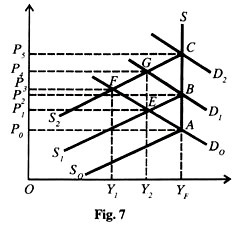

Suppose an inflationary process begins with excess demand with no cost-push forces at work. Excess demand will raise prices which will in due course pull up money wages. But the rise in money wages is not the result of cost-push forces. Such a mixed inflation will lead to sustained rise in prices. This is illustrated in Figure 7.

The initial equilibrium is at YF level of full employment income determined by aggregate demand D0 and aggregate supply S0 S curves at A. The price level is P0 with increase in aggregate demand from D0 to D1 and D2 given the vertical portion of the supply curve S0 S1 prices rise from P0 to P2 to P5, the inflationary path being A, B and C.

This sustained increase in prices has also been the result of the increase in money wage rates due to increase in aggregate demand at the full employment level. When prices rise, producers are encouraged to increase output as their profits rise with increased aggregate demand. They, therefore, raise the demand for labour thereby increasing money wages which further lead to increase in demand for goods and services. So long as the demand for output continues to raise money incomes, inflationary pressures will continue.

Consider an inflationary process that may begin from the supply side due to increase in money wage rates. This will raise prices every time there is a wage-push. But the rise in prices will not be sustained if there is no increase in demand. This is illustrated in Fig. 7 where given the aggregate demand curve D0 a wage-push shifts the supply curve S0 to S1 The new equilibrium is at E.

This raises the price level from P0 to P1 and lowers output and employment to Y2 below the full employment level YF. A further wage-push will again shift the supply curve to S2, and the new equilibrium will be at E, given the demand curve D thereby raising the price level further to P3 and also reducing output and employment to Y1. In the absent of increase in aggregate demand, this cost-push inflationary process will not be a sustained one and will sooner or later come to an end.

The cost-push inflationary process will be self-sustaining only if every wage-push is accompanied by a corresponding increase in aggregate demand. Since every cost-push is accompanied by a fall in output and employment along with a price increase, it is likely that the government will adopt expansionary monetary and fiscal policies in order to check the fall in output and employment.

In this way, cost-push will lead to a sustained inflationary process because the government will try to achieve full employment by raising aggregate demand which will, in turn, lead to further wage-push and so on. Such a situation is again explained with the help of Figure 8. Suppose there is a wage-push at E which shifts the supply curve from S1 to S2 and equilibrium is established at f with the demand curve D0.

The price level rises to P3 and the level to employment is reduced to Y1 When due to an expansionary monetary and fiscal policy, aggregate demand increases to D1 the new equilibrium position is at G where the price level rises to P4 and the level of employment rises to Y. A further increase in demand shifts the aggregate demand curve upward to D2, such that equilibrium is attained at point C where the price level rises to P5 and the economy attains the full employment level YF. Thus a wage-push accompanied by an increase in aggregate demand through expansionary monetary and fiscal policies traces out a ratchet-like inflationary parth from A to E to F to G and to C.

5. Essay on the Sectoral or Demand-Shift Inflation:

Sectoral or demand-shift inflation is associated with the name of Charles Schulz who in a paper, pointed out that the price increases from 1955-57 were caused by neither demand-pull nor cost-push but by sectoral shifts in demand. Schultz advanced his thesis with reference to the American economy but it has now been generalized in the case of modern industrial economies.

Schultz begins his theory by pointing out that prices and wages are flexible upward in response to excess demand but they are rigid downward. Even if the aggregate demand is not excessive, excess demand in some sectors of the economy and deficient demand in other sectors will still lead to a rise in the general price level.

This is because prices do not fall in the deficient-demand sectors, there being downward rigidity of prices. But prices rise in the excess-demand sectors and remain constant in the other sectors. The net effect is an overall rise in the price level.

Moreover, increase in prices in excess-demand industries (or sectors) can spread to deficient-demand industries through the prices of materials and the wages of labour. Excess demand in particular industries will lead to a general rise in the price of intermediate materials, supplies and components. These rising prices of materials will spread to demand-deficient industries which use them as inputs. They will, therefore, raise the prices of their products in order to protect their profit margins.

Not only this, wages will also be bid up in excess demand industries, and wages in demand-deficient industries will follow the rising trend. Because if wages in the latter industries are not raised, they will lead to dissatisfaction among workers, thereby leading to inefficiency and fall in productivity. Thus rising wage rates, originating in the excess demand industries, spread throughout the economy.

The spread of wage increases from excess demand industries to other parts of the economy increases the rise in the price of semi-manufactured materials and components. Other things remaining the same, the influence of increasing costs will be larger at the final stages of production.

Thus producers of finished goods will face a general rise in the level of costs, thereby leading to rising prices. This may happen even in case of those industries which do not have excess demand for the products.

Another reason for demand-shift inflation in modern industrial economies is increase in the relative importance of overhead costs. This increase is due to two factors. First, there is an increase in overhead staff at the expense of production workers.

According to Schultz, automation of production methods, instrumentation of control functions, mechanisation of office and accounting procedures, self-regulating materials, handling equipment’s, etc. lead to the growth of professional and semi-professional personnel in supervising, operating and maintenance roles.

Similarly, the growth of formal research and development (R&D) as a separate function not only alters the production processes but also the composition of the labour force required to service them. These developments lead to the decline in the ratio of production workers to technical and supervisory staff in industries.

The second reason for the rise in overhead costs is that the ratio of relatively short-lived equipment to long-lived plant rises substantially. As a result, depreciation as a proportion of total cost increases. The ultimate effect of an increasing proportion of overhead costs in the total cost is to make average costs more sensitive to variations in output.

The distinguishing characteristic of the demand-shift inflation is a continued investment boom in the face of stable aggregate output. All industries expand their capacity and their employment of overhead personnel yet only a few enjoy a concomitant rise in sales. So producers facing shrinking profit margins try to recover a part of their rising costs in higher prices.

Thus demand-shift inflationary process “arises initially out of excess demand in particular industries. But it results in a general price rise only because of the downward rigidities and cost-oriented nature of prices and wages. It is not characterized by an autonomous upward push of costs nor by an aggregate excess demand. Indeed its basic nature is that it cannot be understood in terms of aggregates alone. Such inflation is the necessary result of sharp changes in the composition of demand, given the structure of prices and wages in the economy.”

This theory was evolved by Schultz to examine the nature of the gradual inflation to which the American economy had been subjected during the period 1955-57. It has since been generalized in the case of modern industrial economies.

Its Criticisms:

Johnson has criticised this theory for two reasons.

First, empirical evidence has failed to confirm Schultz’s proposition that sectoral price increases are explained by upward shifts of demand.

Second, it suffers from the same defects as the two rival theories of demand-pull and cost-push, it seeks to challenge. That is, its “failure to investigate the monetary preconditions for inflation, and imprecision respecting the definitions of full employment and general excess demand.”

6. Essay on the Structural Inflation:

The structuralist school of South America stresses structural rigidities as the principal cause of inflation in such developing countries as Argentina, Brazil, and Chile, Of course, this type of inflation is also to be found in other developing countries.

The structuralists hold the view that inflation is necessary with growth. According to this view, as the economy develops, rigidities arise which lead to structural inflation. In the initial phase, there are increases in non-agricultural incomes accompanied by high growth rate of population that tend to increase the demand for goods.

In fact, the pressure of population growth and rising urban incomes would tend to raise through a chain reaction mechanism, first the prices of agricultural goods, second, the general price level, and third, wages.

Let us analyse them below:

1. Agricultural Goods:

As the demand for agricultural goods rises, their domestic supply being inelastic, the prices of agricultural goods rise. The output of these goods does not increase when their prices rise because their production is inelastic due to a defective system of land tenure and other rigidities in the form of lack of irrigation, finance, storage and marketing facilities, and bad harvests.

To prevent the continuous rise in agricultural products, especially foods products, they can be imported. But it is not possible to import them in large quantities due to foreign exchange constraint. Moreover, the prices of imported products are relatively higher than their domestic prices. This tends to raise the price level further within the economy.

2. Wage Increases:

When the prices of food products rise, wage earners press for increase in wage rates to compensate for the fall in their real incomes. But wages and/or D.A. are linked to the cost of living index. They are, therefore, raised whenever the cost of living index rises above an agreed point which further increases the demand for goods and a further rise in their prices.

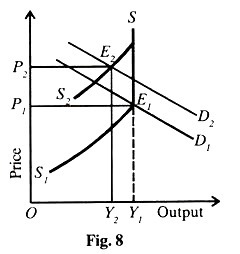

The effect of increase in the wage rates on prices in illustrated in Figure 8. When wage rates rise, the aggregate demand for goods increases from D1 to D2. But the aggregate supply falls due to increase in labour costs which results in the shifting of aggregate supply curve from S1S to S2S. Since the production of goods is inelastic due to structural rigidities after a point, the supply curve is shown as vertical from point onward.

The initial equilibrium is at E1 where the curves D1 and S1 intersect at the output level OY, and the price level is OP1 When supply falls due to increase in labour costs, the supply curve shifts from S1 to S2 and it intersects the demand curve D2 at E2 and production falls from OY1 to OY2 and the price level rises from OP1 to OP3

3. Import Substitution:

Another cause of structural inflation is that the rate of export growth in a developing economy is slow and unstable which is inadequate to support the required growth rate of the economy. The sluggish growth rate of exports and the foreign exchange constraint lead to the adoption of the policy of industrialisation based on import substitution.

Such a policy necessitates the use of protective measures which, in turn, tend to raise the prices of industrial products, and incomes in the non-agricultural sectors, thereby leading to further rise in prices. Moreover, this policy leads to a cost-push rise in prices because of the rise in prices of imported materials and equipment, and protective measures.

The policy of import substitution also tends to be inflationary because of the relative inefficiency of the new industries during the “learning” period. The secular deterioration in the terms of trade of primary products of developing countries further limits the growth of income from exports which often leads to the exchange rate devaluation.

4. Tax System:

The nature of the tax systems and budgetary processes also help in accentuating the inflationary trends in such economies. The tax system has low inflation elasticities which means that when prices rise, the real value of taxes falls.

Often taxes are fixed in money terms or they are raised slowly to adjust for price rises. Moreover, it often takes long time to collect taxes with the result that by the time they are paid by assessees, their real value is less to the exchequer.

On the other hand, planned expenditures on projects are often not incurred on schedule due to various supply bottlenecks with the result that when prices rise, the money value of expenditures rises proportionately. As a result of fall in the real value of tax collections and rise in money value of expenditures, governments have to adopt larger fiscal deficits which further accentuate inflationary pressures.

5. Money Supply:

So far as the money supply is concerned, it automatically expands when prices rise in a developing country. As prices rise, firms need larger funds from banks. And the government needs more money to finance larger deficits in order to meet its expanding expenditure and wages of its employees.

For this, it borrows from the central bank which leads to monetary expansion and to a further rise in the rate of inflation. Thus structural inflation may result from supply in-elasticities leading to rise in agricultural prices, costs of import substitutes, deterioration of the terms of trade and exchange rate devaluation.

Its Criticisms:

The basic weaknesses in the structural arguments have been:

First, no separation is made between autonomous structural rigidities and induced rigidities resulting from price and exchange controls or mismanagement of government intervention.

Second, the sluggishness in the export growth is not really structural but the result of failure to exploit export opportunities because of overvalued exchange rates.

7. Essay on the Markup Inflation:

The theory of markup inflation is mainly associated with Prof. Ackley, though formal models have also been presented by Holzman and Duesenberry independently of each other. We analyse below Ackley’s simplified version of the markup inflation.

The analysis is based on the assumption that both wages and prices are “administered” and are settled by workers and business firms. Firms fix administrative prices for their goods by adding to their direct material and labour costs, and some standard markup which covers profit Labour also seeks wages on the basis of a fixed markup over its cost of living.

This model of inflation can lead to either a stable, a rising, or a falling price level depending on the markups which firms and workers respectively use. If either or both use a percentage markup, the inflation will progress faster than if either or both fix the markups in money terms. If each participant fixes prices on the basis of prices he pays, the inflation will be high and of long duration.

If one firm raises its prices in order to maintain its desired markup, the costs of other firms are raised which, in turn, raise their prices and this process of raising costs and prices will spread to other firms in an endless chain. When consumers buy such goods whose prices are rising, their cost of living rises. This causes wage costs to rise, thereby increasing the inflationary spiral. However, the inflationary spiral may come to a halt, if there is a gradual improvement in the efficiency and productivity of labour.

A rise in efficiency and productivity means that there is a rise in wage rates or prices of materials leading to a smaller rise in labour and material costs. But stability in prices may not come if firms and workers appropriate the gains of rising productivity by increasing their markups. If each participant increases its markup by 100 per cent of the gains of productivity increase, the inflationary spiral might continue indefinitely.

According to Ackley, the markup can be based on either historical experience or expectations of future costs and prices. Moreover, the size of the markup applied by firms and workers is a function of the pressure of demand felt in the economy.

When the demand is moderate, the markups may by applied to historically experienced costs and prices, and the price rise may be slow. But when demand is intense, the markups are based on anticipations of future costs, and prices rise rapidly. Thus there can be no inflation without some change in the size of the markup.

This theory can also be applied to cost-push and demand-pull models of inflation. If firms and workers believe that their markups are lower than the required costs and prices, regardless of the state of aggregate demand, they will increase the size of their markups. Under such a situation, costs and prices rise in an inflationary spiral. This is similar to the cost-push inflation. On the other hand, if firms and workers raise the markups due to increase in demand, markup pricing is related to demand-pull inflation.

To conclude with Ackley, “Inflation might start from an initial autonomous increase either in business and labour markups. Or it might start from an increase in aggregate demand and which first and most directly affected some of the flexible market-determined prices. But however it starts, the process involves the interaction of demand and market elements.”

The markup inflation can be controlled by the usual monetary and fiscal tools in order to restrict the demand for goods and increase productivity. Ackley also suggests wage-and-price guidelines or an incomes policy to be administered by a national wage-and-price commission.

Its Criticisms:

Ackley’s theory suffers from two weaknesses:

First, the theory gives a very limited explanation of the cause of inflation, especially the motives which compel workers and firms to fix higher markups in the absence of demand conditions.

Second, it suffers from the implication that once inflation starts, it is likely to continue indefinitely when costs and prices rise in a spiral.

8. Essay on the Causes of Inflation:

Inflation is caused when aggregate demand exceeds aggregate supply of goods and services. We analyse the factors which lead to increase in demand and shortage of supply.

Factors Affecting Demand:

Both Keynesians and monetarists believe that inflation is caused by increase in aggregate demand. They point toward the following factors which raise it.

1. Increase in Money Supply:

Inflation is caused by an increase in the supply of money which leads to increase in aggregate demand. The higher the growth rate of the nominal money supply, the higher is the rate of inflation. Modern quantity theorists do not believe that true inflation starts after the full employment level. This view is realistic because all advanced countries are faced with high levels of unemployment and high rates of inflation.

2. Increase in Disposable Income:

When the disposable income of the people increases, it raises their demand for goods and services. Disposable income may increase with the rise in national income or reduction in taxes or reduction in the saving of the people.

3. Increase in Public Expenditure:

Government activities have been expanding much with the result that government expenditure has also been increasing at a phenomenal rate, thereby raising aggregate demand for goods and services. Governments of both developed and developing countries are providing more facilities under public utilities and social services, and also nationalizing industries and starting public enterprises with the result that they help in increasing aggregate demand.

4. Increase in Consumer Spending:

The demand for goods and services increases when consumer expenditure increases. Consumers may spend more due to conspicuous consumption or demonstration effect. They may also spend more when they are given credit facilities to buy goods on hire-purchase and instalment basis.

5. Cheap Monetary Policy:

Cheap monetary policy or the policy of credit expansion also leads to increase in the money supply which raises the demand for goods and services in the economy. When credit expands, it raises the money income of the borrowers which, in turn, raises aggregate demand relative to supply, thereby leading to inflation. This is also known as credit-induced inflation.

6. Deficit Financing:

In order to meet its mounting expenses, the government resorts to deficit financing by borrowing from the public and even by printing more notes. This raises aggregate demand in relation to aggregate supply, thereby leading to inflationary rise in prices. This is also known as deficit-induced inflation.

7. Expansion of the Private Sector:

The expansion of the private sector also tends to raise the aggregate demand. For huge investments increase employment and income, thereby creating more demand for goods and services. But it takes time for the output to enter the market. This leads to rise in prices.

8. Black Money:

The existence of black money in all countries due to corruption, tax evasion etc. increases the aggregate demand. People spend such unearned money extravagantly, thereby creating unnecessary demand for commodities. This tends to raise the price level further.

9. Repayment of Public Debt:

Whenever the government repays its past internal debt to the public, it leads to increase in the money supply with the public. This tends to raise the aggregate demand for goods and services and to rise in prices.

10. Increase in Exports:

When the demand for domestically produced goods increases in foreign countries, this raises the earnings of industries producing export commodities. These, in turn, create more demand for goods and services within the economy, thereby leading to rise in the price level.

Factors Affecting Supply:

There are also certain factors which operate on the opposite side and tend to reduce the aggregate supply.

Some of the factors are as follows:

1. Shortage of Factors of Production:

One of the important causes affecting the supplies of goods is the shortage of such factors as labour, raw materials, power supply, capital, etc. They lead to excess capacity and reduction in industrial production, thereby raising prices.

2. Industrial Disputes:

In countries where trade unions are powerful, they also help in curtailing production. Trade unions resort to strikes and if they happen to be unreasonable from the employers’ viewpoint and are prolonged, they force the employers to declare lock-outs. In both cases, industrial production falls, thereby reducing supplies of goods. If the unions succeed in raising money wages of their members to a very high level than the productivity of labour, this also tends to reduce production and supplies of goods. Thus they tend to raise prices.

3. Natural Calamities:

Drought or floods is a factor which adversely affects the supplies of agricultural products. The latter, in turn, create shortages of food products and raw materials, thereby helping inflationary pressures.

4. Artificial Scarcities:

Artificial scarcities are created by hoarders and speculators who indulge in black marketing. Thus they are instrumental in reducing supplies of goods and raising their prices.

5. Increase in Exports:

When the country produces more goods for export than for domestic consumption, this creates shortages of goods in the domestic market. This leads to inflation in the economy.

6. Lop-sided Production:

If the stress is on the production of comfort, luxury, or basic products to the neglect of essential consumer goods in the country, this creates shortages or consumer goods. This again causes inflation.

7. Law of Diminishing Returns:

If industries in the country are using old machines and outmoded methods of production, the law of diminishing returns operates. This raises cost per unit of production, thereby raising the prices of products.

8. International Factors:

In modern times, inflation is a worldwide phenomenon. When prices rise in major industrial countries, their effects spread to almost all countries with which they have trade relations. Often the rise in the price of a basic raw material like petrol in the international market leads to rise in the prices of all related commodities in a country.

9. Essay on the Effects of Inflation:

Inflation affects different people differently. This is because of the fall in the value of money. When price rises or the value of money falls, some groups of the society gain, some lose and some stand in-between. Broadly speaking, there are two economic groups in every society, the fixed income group and the flexible income group. People belonging to the first group lose and those belonging to the second group gain.

The reason is that the price movements in the case of different goods, services, assets, etc. are not uniform. When there is inflation, most prices are rising, but the rates of increase of individual prices differ much. Prices of some goods and services rise faster, of others slowly and of still others remain unchanged. We discuss below the effects of inflation on redistribution of income and wealth, production, and on the society as a whole.

1. Effects on Redistribution of Income and Wealth:

There are two ways to measure the effects of inflation on the redistribution of income and wealth in a society.

First, on the basis of the change in the real value of such factor incomes as wages, salaries, rents, interest, dividends and profits.

Second, on the basis of the size distribution of income over time as a result of inflation, i.e. whether the incomes of the rich have increased and that of the middle and poor classes have declined with inflation. Inflation brings about shifts in the distribution of real income from those whose money incomes are relatively inflexible to those whose money incomes are relatively flexible.

The poor and middle classes suffer because their wages and salaries are more or less fixed but the prices of commodities continue to rise. They become more impoverished. On the other hand, businessmen, industrialists, traders, real estate holders, speculators, and others with variable incomes gain during rising prices. The latter category of persons become rich at the cost of the former group. There is unjustified transfer of income and wealth from the poor to the rich.

As a result, the rich roll in wealth and indulge in conspicuous consumption, while the poor and middle classes live in abject misery and poverty. But which income group of society gains or loses from inflation depends on who anticipates inflation and who does not.

Those who correctly anticipate inflation, they can adjust their present earnings, buying, borrowing, and lending activities against the loss of income and wealth due to inflation. They, therefore, do not get hurt by the inflation. Failure to anticipate inflation correctly leads to redistribution of income and wealth.

In practice, all persons are unable to anticipate and predict the rate of inflation correctly so that they cannot adjust their economic behaviour accordingly. As a result, some persons gain while others lose. The net result is redistribution of income and wealth.

The effects of inflation on different groups of society are discussed below:

(1) Debtors and Creditors:

During periods of rising prices, debtors gain and creditors lose. When prices rise, the value of money falls. Though debtors return the same amount of money, but they pay less in terms of goods and services. This is because the value of money is less than when they borrowed the money. Thus the burden of the debt is reduced and debtors gain. On the other hand, creditors lose. Although they get back the same amount of money which they lent, they receive less in real terms because the value of money falls. Thus inflation brings about a redistribution of real wealth in favour of debtors at the cost of creditors.

(2) Salaried Persons:

Salaried workers such as clerks, teachers, and other white collar persons lose when there is inflation. The reason is that their salaries are slow to adjust when prices are rising.

(3) Wage Earners:

Wage earners may gain or lose depending upon the speed with which their wages adjust to rising prices. If their unions are strong, they may get their wages linked to the cost of living index. In this way, they may be able to protect themselves from the bad effects of inflation.

But the problem is that there is often a time lag between the raising of wages by employees and the rise in prices. So workers lose because by the time wages are raised, the cost of living index may have increased further. But where the unions have entered into contractual wages for a fixed period, the workers lose when prices continue to rise during the period of contract. On the whole, the wage earners are in the same position as the white collar persons.

(4) Fixed Income Group:

The recipients of transfer payments such as pensions, unemployment insurance, social security, etc. and recipients of interest and rent have on fixed incomes. Pensioners get fixed pensions. Similarly the rentier class consisting of interest and rent receivers get fixed payments.

The same is the case with the holders of fixed interest bearing securities, debentures and deposits. All such persons lose because they receive fixed payments, while the value of money continues to fall with rising prices. Among these groups, the recipients of transfer payments belong to the lower income group and the rentier class to the upper income group. Inflation redistributes income from these two groups toward the middle income group comprising traders and businessmen.

(5) Equity Holders or Investors:

Persons who hold shares or stocks of companies gain during inflation. For when prices are rising business activities expand which increase profits of companies. As profits increase, dividends on equities also increase at a faster rate than prices. But those who invest in debentures, securities, bonds, etc. which carry a fixed interest rate lose during inflation because they receive a fixed sum while the purchasing power is falling.

(6) Businessmen:

Businessmen of all types, such as producers, traders and real estate holders gain during periods of rising prices. Take producers first. When prices are rising, the value of their inventories (goods in stock) rise in the same proportion. So they profit more when they sell their stored commodities. The same is the case with traders in the short run. But producers profit more in another way.

Their costs do not rise to the extent of the rise in the prices of their goods. This is because prices of raw materials and other inputs and wages do not rise immediately to the level of the price rise. The holders of real estates also profit during inflation because the prices of landed property increase much faster than the general price level.

(7) Agriculturists:

Agriculturists are of three types, landlords, peasant proprietors, and landless agricultural workers. Landlords lose during rising prices be-caused they get fixed rents. But peasant proprietors who own and cultivate their farms gain. Prices of farm products increase more than the cost of production.

For prices of inputs and land revenue do not rise to the same extent as the rise in the prices of farm products. On the other hand, the landless agricultural workers are hit hard by rising prices. Their wages are not raised by the farm owners, because trade unionism is absent among them. But the prices of consumer goods rise rapidly. So landless agricultural workers are losers.

(8) Government:

The government as a debtor gains at the expense of households who are its principal creditors. This is because interest rates on government bonds are fixed and are not raised to offset expected rise in prices. The government, in turn, levies less taxes to service and retire its debt. With inflation, even the real value of taxes is reduced.

Thus redistribution of wealth in favour of the government accrues as a benefit to the tax-payers. Since the tax-payers of the government are high-income groups, they are also the creditors of the government because it is they who hold government bonds. As creditors, the real value of their assets decline and as tax-payers, the real value of their liabilities also declines during inflation. The extent to which they will be gainers or losers on the whole is a very complicated calculation.

Conclusion:

Thus inflation redistributes income from wage earners and fixed income groups to profit recipients, and from creditors to debtors. So far as wealth redistributions are concerned, the very poor and the very rich are more likely to lose than middle income groups.

This is because the poor hold what little wealth they have in monetary form and have few debts, whereas the very rich hold a substantial part of their wealth in bonds and have relatively few debts. On the other hand, the middle income groups are likely to be heavily in debt and hold some wealth in common stocks as well as in real assets.

2. Effects on Production:

When prices start rising production is encouraged. Producers earn wind-fall profits in the future. They invest more in anticipation of higher profits in the future. This tends to increase employment, production and income. But this is only possible up to the full employment level.

Further increase in investment beyond this level will lead to severe inflationary pressures within the economy because prices rise more than production as the resources are fully employed. So inflation adversely affects production after the level of full employment.

The adverse effects of inflation on production are discussed below:

(1) Misallocation of Resources:

Inflation causes misallocation of resources when producers divert resources from the production of essential to non-essential goods from which they expect higher profits.

(2) Changes in the System of Transactions:

Inflation leads to changes in transactions pattern of producers. They hold a smaller stock of real money holdings against unexpected contingencies than before. They devote more time and attention to converting money into inventories or other financial or real assets. It means that time and energy are diverted from the production of goods and services and some resources are used wastefully.

(3) Reduction in Production:

Inflation adversely affects the volume of production because the expectation of rising prices along-with rising costs of inputs bring uncertainty. This reduces production.

(4) Fall in Quality:

Continuous rise in prices creates a seller’s market. In such a situation, producers produce and sell sub-standard commodities in order to earn higher profits. They also indulge in adulteration of commodities.

(5) Hoarding and Black marketing:

To profit more from rising prices, producers hoard stocks of their commodities. Consequently, an artificial scarcity of commodities is created in the market. Then the producers sell their products in the black market which increases inflationary pressures.

(6) Reduction in Saving:

When prices rise rapidly, the propensity to save declines because more money is needed to buy goods and services than before. Reduced saving adversely affects investment and capital formation. As a result, production is hindered.

(7) Hinders Foreign Capital:

Inflation hinders the inflow of foreign capital because the rising costs of materials and other inputs make foreign investment less profitable.

(8) Encourages Speculation:

Rapidly rising prices create uncertainty among producers who indulge in speculative activities in order to make quick profits. Instead of engaging themselves in productive activities, they speculate in various types of raw materials required in production.

3. Other Effects:

Inflation leads to a number of other effects which are discussed as under:

(1) Government:

Inflation affects the government in various ways. It helps the government in financing its activities through inflationary finance. As the money incomes of the people increase, government collects that in the form of taxes on incomes and commodities. So the revenues of the government increase during rising prices.

Moreover, the real burden of the public debt decreases when prices are rising. But the government expenses also increase with rising production costs of public projects and enterprises and increase in administrative expenses as prices and wages rise. On the whole, the government gains under inflation because rising wages and profits spread an illusion of prosperity within the country.

(2) Balance of Payments:

Inflation involves the sacrificing of the advantages of international specialisation and division of labour. It affects adversely the balance of payments of a country. When prices rise more rapidly in the home country than in foreign countries, domestic products become costlier compared to foreign products.

This tends to increase imports and reduce exports, thereby making the balance of payments unfavourable for the country. This happens only when the country follows a fixed exchange rate policy. But there is no adverse impact on the balance of payments if the country is on the flexible exchange rate system.

(3) Exchange Rate:

When prices rise more rapidly in the home country than in foreign countries, it lowers the exchange rate in relation to foreign currencies.

(4) Collapse of the Monetary System:

If hyperinflation persists and the value of money continues to fall many times in a day, it ultimately leads to the collapse of the monetary system, as happened in Germany after World War 1.

(5) Social. Inflation is socially harmful:

By widening the gulf between the rich and the poor, rising prices create discontentment among the masses. Pressed by the rising cost of living, workers resort to strikes which lead to loss in production. Lured by profits, people resort to hoarding, black marketing, adulteration, manufacture of substandard commodities, speculation, etc. Corruption spreads in every walk of life. All this reduces the efficiency of the economy.

(6) Political:

Rising prices also encourage agitations and protests by political parties opposed to the government. And if they gather momentum and become unhandy they may bring the downfall of the government. Many governments have been sacrificed at the alter of inflation.

Inflation as a Tax:

Inflation operates like a tax when redistribution results in goods and services being transferred to the government from the people. If falls heavily on those least able to pay. When the government issues more money to finance its budget deficit, to repay its past debt and to meet its rising demand for goods and services during inflation, it acts as a tax on the people and it transfers purchasing power to the government.

High inflation rates decrease the purchasing power of money with the people and discourage them from holding money. The rate of inflation is the rate of inflation tax. The inflation tax is defined as the decline in purchasing power of money due to inflation.

It is calculated as:

m x i/ (1+ i)

Where M is the average money at year-ending and year-beginning and i is the decimal inflation rate measured by the change in consumer price index (CPI). The formula tells that the period for which prices rise by i, each money unit loses i/ (1+i) of its purchasing power.

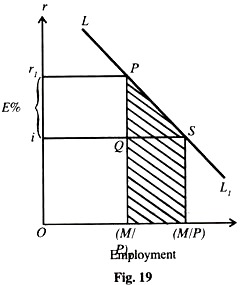

Inflation as a tax on holding real money balances is explained in terms of Figure 19, where the level of real money balances is measured on the horizontal axis and the interest rate on the vertical axis. Suppose the government issues money to finance its budget deficit which will raise the price level and cause the real money stock to fall.

Assuming that the initial price level is stable, and the level of real income is constant, the money interest rate (i) is equal to the real interest rate (r). We begin the analysis by further assuming zero expected rate of inflation which is equal to the money interest rate (i). In such as economy, the demand for real money balances as a function of the money interest rate is shown by the curve LL1 If the money interest rate consistent with the stable price level is i, the amount of real money balances people wish to hold is (M/P).

If the expected rate of inflation is E%, the interest rate rises to r and the level of real cash balances falls from (M/P) to (M/P)r This means that as soon as the government announces the expected rate of inflation to be E% (i-r1), everybody desiring to reduce his real cash balances will purchase physical assets and stocks of consumer and other goods, and the price level will rise in the proportion (M/P)/ (M/P). The proceeds of the tax in real terms are equal to the rectangle r, PQ i which is the inflation tax revenue to the government. The tax base is the amount of real money held by the public which is (M/P)1 (= iQ), and the tax rate is the inflation rate (i-r1)

As a result of high inflation rate, the asset holders pay the inflation tax by losing purchasing power on their money holdings. The government as the issuer of money collects the tax in the form of a reduction in the real value of its liabilities. When the government pays interest on these liabilities, it returns some of the tax to holders of money.

In practice, central banks do not pay so much interest as to offset the tax on the money issued by them. They pay no interest on currency and usually pay an interest rate on reserves below the market rate.

10. Essay on the Costs of Inflation:

The costs of inflation may be economic or social loss arising from the effects of inflation. Assuming that people hold only non-interest bearing money in the form of currency issued by the government and demand deposits of banks, the costs of inflation refer to the loss in real money balances held by individuals and businesses. Since money does not bear a rate of interest, the opportunity cost of holding money rises with the inflation rate which, in turn, reduces the demand for real money balances.

Individuals and business enterprises hold cash balances because they yield utility to them. At a higher rate of inflation, they find the purchasing power of the money balances diminishing. In other words, they find that they require more real money balances than before when there is inflation.

The costs of inflation arise when they try to change their existing system of transactions or payments to adjust to a smaller stock of real cash holdings. Individuals or households visit the markets more frequently to buy goods. Business enterprises visit banks more often, increase the frequency of ordering inventories, devote more time and attention in converting money into inventories or financial and real assets.

Thus the change in the transactions or payments patterns of individuals and business enterprises require more time and energy then before. It leads to the diversion of resources from productive to unproductive uses when they are required to visit markets and banks more frequently, maintain excessive inventories of consumer and producer goods, etc.

When the real money balances with the people are reduced due to higher expected rate of inflation, their peace of mind is also disturbed. Thus “the ultimate social cost of anticipated inflation is the wasteful use of resources to economise holdings of currency and other non-interest bearing means of payment.”

Another social cost of inflation is in terms of the Phillips curve analysis. When inflation starts and is expected to continue, any attempt to reduce its rate of increase will lead to more unemployment. Increase in unemployment is a loss to the economy in terms of the goods and services which cannot be produced because people available for employment are not used.

The majority of economists also regard the redistributive effects of inflation as the cost of inflation. The social cost of inflation can be measured in terms of Figure 20. The curve LL1 is the demand curve for real cash balances which can be interpreted as the MP (utility) curve of real cash balances. When the rate of inflation is zero, the real interest rate is equal to the money interest rate at i. The demand for real cash balances is (M/P).

The area under the demand curve LL1 over a given segment of the horizontal axis measures the flow of productivity (utility) from the indicated quantity of real money balances. When inflation increases at the expected rate of E% (i-r1) the interest rate rises from i to r, and the demand for real cash balances falls to (M/ P)r

This reduction in real cash balances by (M/P)-(M/P)1 is the social cost of inflation which is measured by the shaded area (M/P)1 PS (M/P). This area “measures the aggregate loss of productivity (utility) resulting from the destruction of real cash balances which occurs when prices rise initially at the announcement that there will be an inflation. The further rise of prices representing the inflation itself is merely sufficient to keep real balances at their new low level and so guarantee that this loss of productivity (utility) will continue as long as the inflation does.”

11. Essay on the Measures to Control Inflation:

We have studied above that inflation is caused by the failure of aggregate supply to equal the increase in aggregate demand. Inflation can, therefore, be controlled by increasing the supplies of goods and services and reducing money incomes in order to control aggregate demand. The various methods are usually grouped under three heads: monetary measures, fiscal measures and other measures.

Monetary Measures:

Monetary measures aim at reducing money incomes.

(a) Credit Control:

One of the important monetary measures is monetary policy. The central bank of the country adopts a number of methods to control the quantity and quality of credit. For this purpose, it raises the bank rates, sells securities in the open market, raises the reserve ratio, and adopts a number of selective credit control measures, such as raising margin requirements and regulating consumer credit. Monetary policy may not be effective in controlling inflation, if inflation is due to cost-push factors. Monetary policy can only be helpful in controlling inflation due to demand-pull factors.

(b) Demonetisation of Currency:

However, one of the monetary measures is to demonetise currency of higher denominations. Such a measures is usually adopted when there is abundance of black money in the country.

(c) Issue of New Currency:

The most extreme monetary measure is the issue of new currency in place of the old currency. Under this system, one new note is exchanged for a number of notes of the old currency. The value of bank deposits is also fixed accordingly. Such a measure is adopted when there is an excessive issue of notes and there is hyperinflation in the country. It is a very effective measure. But is inequitable for its hurts the small depositors the most.

Fiscal Measures:

Monetary policy alone is incapable of controlling inflation. It should, therefore, be supplemented by fiscal measures. Fiscal measures are highly effective for controlling government expenditure, personal consumption expenditure, and private and public investment.

The principal fiscal measures are the following:

(a) Reduction in Unnecessary Expenditure:

The government should reduce unnecessary expenditure on non-development activities in order to curb inflation. This will also put a check on private expenditure which is dependent upon government demand for goods and services. But it is not easy to cut government expenditure. Though this measure is always welcome but it becomes difficult to distinguish between essential and nonessential expenditure. Therefore, this measure should be supplemented by taxation.

(b) Increase in Taxes:

To cut personal consumption expenditure, the rates of personal, corporate and commodity taxes should be raised and even new taxes should be levied, but the rates of taxes should not be so high as to discourage saving investment and production.

Rather, the tax system should provide larger incentives to those who save, invest and produce more. Further, to bring more revenue into the tax-net, the government should penalize the tax evaders by imposing heavy fines. Such measures are bound to be effective in controlling inflation. To increase the supply of goods within the country, the government should reduce import duties and increase export duties.

(c) Increase in Savings:

Another measure is to increase savings on the part of the people. This will tend to reduce disposable income with the people, and hence personal consumption expenditure. But due to the rising cost of living, people are not in a position to save much voluntarily.

Keynes, therefore, advocated compulsory savings or what he called ‘deferred payment’ where the saver gets his money back after some years. For this purpose, the government should float public loans carrying high rates of interest, start saving schemes with prize money, or lottery for long periods, etc. It should also introduce compulsory provident fund, provident fund-cum-pension schemes, etc. All such measures increase savings and are likely to be effective in controlling inflation.

(d) Surplus Budgets:

An important measure is to adopt anti-inflationary budgetary policy. For this purpose, the government should give up deficit financing and instead have surplus budgets. It means collecting more in revenues and spending less.

(e) Public Debt:

At the same time, it should stop repayment of public debt and postpone it to some future date till inflationary pressures are controlled within the economy. Instead, the government should borrow more to reduce money supply with the public.

Like monetary measures, fiscal measures alone cannot help in controlling inflation. They should be supplemented by monetary, non-monetary and non-fiscal measures.

Other Measures:

The other types of measures are those which aim at increasing aggregate supply and reducing aggregate demand directly.

(a) To Increase Production:

The following measures should be adopted to increase production:

(i) One of the foremost measures to control inflation is to increase the production of essential consumer goods like food, clothing, kerosene oil, sugar, vegetable oils, etc.

(ii) If there is need, raw materials for such products may be imported on preferential basis to increase the production of essential commodities,